POETRY GRADE 12 NOTES - LITERATURE STUDY GUIDE

Share via Whatsapp Join our WhatsApp Group Join our Telegram Group- POETRY OVERVIEW

- SONNET 116 BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

- DEATH BE NOT PROUD BY JOHN DONNE

- AN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL CLASSROOM IN A SLUM BY STEPHEN SPENDER

- AUTO WRECK BY KARL SHAPIRO

- ON HIS BLINDNESS BY JOHN MILTON

- A PRAYER FOR ALL MY COUNTRYMEN BY GUY BUTLER

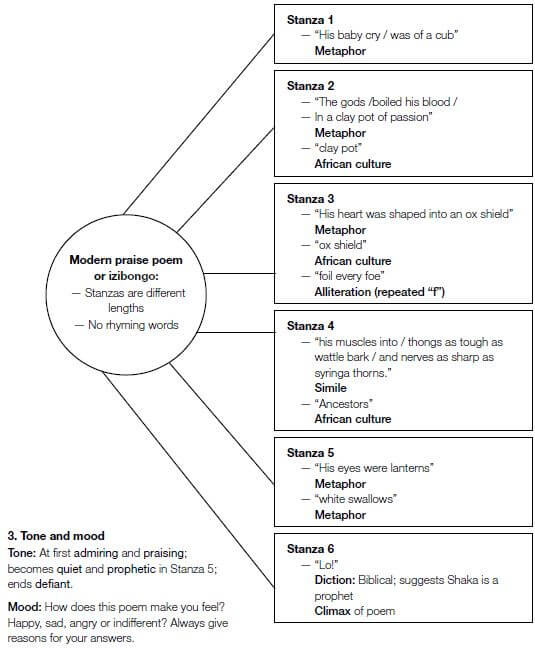

- THE BIRTH OF SHAKA BY OSWALD MBUYISENI MTSHALI

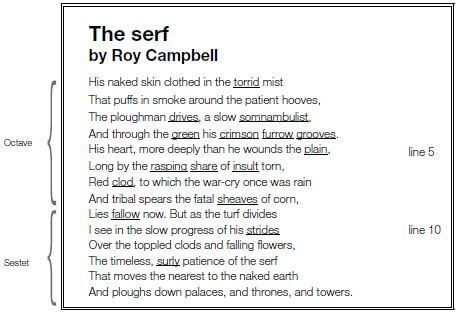

- THE SERF BY ROY CAMPBELL

- MEMENTOS, 1 BY WD SNODGRASS

- CHEETAH BY CHARLES EGLINGTON

POETRY OVERVIEW

Dear Grade 12 learner

This Mind the Gap study guide helps you to prepare for the end-of-year Grade 12 English First Additional Language (EFAL) Literature exam.

There are three exams for EFAL: Paper 1: Language in Context; Paper 2: Literature; and Paper 3: Writing.

There are nine great EFAL Mind the Gap study guides which cover Papers 1, 2 and 3.

Paper 2: Literature includes the study of novels, drama, short stories and poetry. A Mind the Gap study guide is available for each of the prescribed literature titles. Choose the study guide for the set works you studied in your EFAL class at school.

This study guide focuses on the 10 prescribed poems examined in Paper 2: Literature. You will need to study all 10 poems for the exam:

- Sonnet 116 by William Shakespeare

- Death be not proud by John Donne

- An elementary school classroom in a slum by Stephen Spender

- Auto wreck by Karl Shapiro

- On his blindness by John Milton

- A prayer for all my countrymen by Guy Butler

- The birth of Shaka by Oswald Mbuyiseni Mtshali

- The serf by Roy Campbell

- Mementos, 1 by WD Snodgrass

- Cheetah by Charles Eglington

How to use this study guide

There is one chapter for each poem. Each chapter includes a copy of the poem and information about:

- The poet;

- The themes;

- Words you need to know to understand the poem;

- Type and form;

- Line-by-line analysis; and

- Tone and mood.

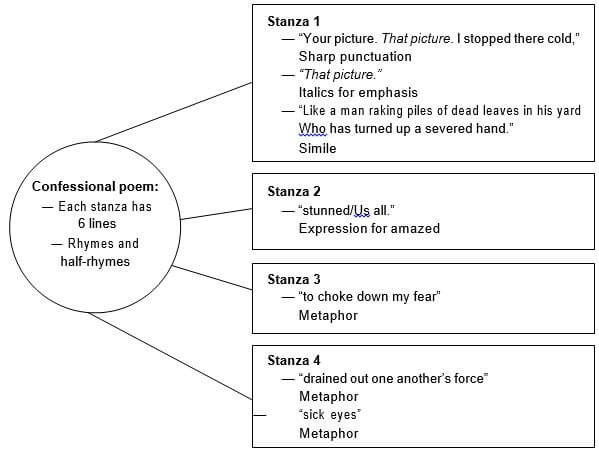

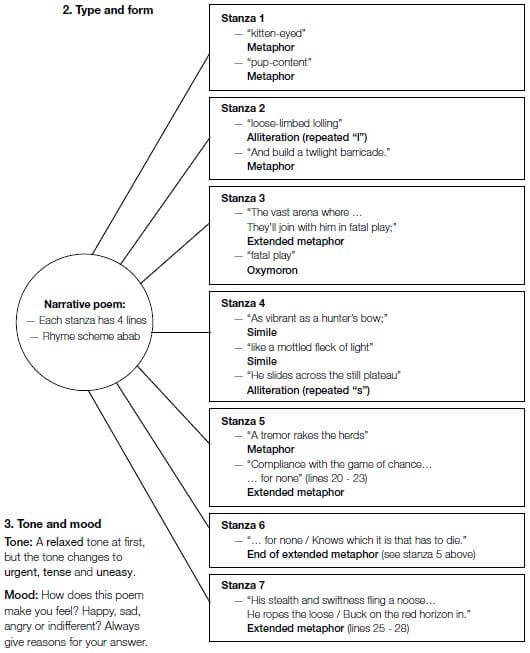

All the above information is contained in a one-page summary. Use the 10 summaries to help you hold the 10 poems clearly in your mind.

You can test your understanding of each poem by completing the activities, then use the answers to mark your own work. The activities are based on the kinds of questions you will find in the exam.

Top 7 study tips

- Break your learning up into manageable sections. This will help your brain to focus. Take short breaks between studying one section and going onto the next.

- Have all your materials ready before you begin studying a section – pencils, pens, highlighters, paper, glass of water, etc.

- Be positive. It helps your brain hold on to the information.

- Your brain learns well with colours and pictures. Try to use them whenever you can.

- Repetition is the key to remembering information you have to learn. Keep going over the work until you can recall it with ease.

- Teach what you are learning to anyone who will listen. It is definitely worth reading your revision notes aloud.

- Sleeping for at least eight hours every night, eating healthy food and drinking plenty of water are all important things you need to do for your brain. Studying for exams is like exercise, so you must be prepared physically as well as mentally.

On the exam day

- Make sure you bring pens that work, sharp pencils, a rubber and a sharpener. Make sure you bring your ID document and examination admission letter. Arrive at the exam venue at least an hour before the start of the exam.

- Go to the toilet before entering the exam room. You don’t want to waste valuable time going to the toilet during the exam.

- You must know at the start of the exam which two out of the four sections of the Paper 2 Literature exam you will be answering. Use the 10 minutes’ reading time to read the instructions carefully.

- Break each question down to make sure you understand what is being asked. If you don’t answer the question properly you won’t get any marks for it. Look for the key words in the question to know how to answer it. You will find a list of question words on pages xiv and xv of this study guide.

- Manage your time carefully. Start with the question you think is the easiest. Check how many marks are allocated to each question so you give the right amount of information in your answer.

- Remain calm, even if the question seems difficult at first. It will be linked with something you have covered. If you feel stuck, move on and come back if time allows. Do try and answer as many questions as possible.

- Take care to write neatly so the examiners can read your answers

Overview of the English First Additional Language Paper 2: Literature exam

In the Paper 2 Literature exam, you need to answer questions from two sections. Choose the two sections that you know best:

- Section A: Novel

- Section B: Drama

- Section C: Short stories

- Section D: Poetry

A total of 70 marks is allocated for Paper 2, which means 35 marks for each section you choose.

You will have two hours for this exam.

Here is a summary of the Paper 2 Literature exam paper:

Question number | Title of novel | Type of question | Number of marks |

Section A: Novel If you choose Section A, answer ONE question. Choose the question for the book you have learnt. | |||

1. | To Kill a Mockingbird | Contextual | 35 |

2. | Lord of the Flies | Contextual | 35 |

3. | A Grain of Wheat | Contextual | 35 |

Section B: Drama If you choose Section B, answer ONE question. Choose the question for the play you have learnt. | |||

4. | Romeo and Juliet | Contextual | 35 |

5. | Nothing but the Truth | Contextual | 35 |

Section C: Short stories If you choose Section C, answer BOTH questions. You will not know exactly which short stories are included until the exam. TWO stories will be set. Answer the questions set on BOTH short stories. | |||

6.1 | Short story | Contextual | 17 or 18 |

6.2 | Short story | Contextual | 17 or 18 |

Section D: Poetry If you choose Section D, answer BOTH questions. You will not know exactly which poems are included until the exam. TWO poems will be set. Answer the questions set on BOTH poems. | |||

7.1 | Poem | Contextual | 17 or 18 |

7.2 | Poem | Contextual | 17 or 18 |

What is a contextual question?

In a contextual question, you are given an extract from the poem. You then have to answer questions based on the extract. Some answers you can find in the extract. Other questions will test your understanding of other parts of the poem. Some questions ask for your own opinion about the poem.

What are the examiners looking for?

Examiners will assess your answers to the contextual questions based on:

- Your understanding of the literal meaning of the poem. You need to identify information that is clearly given in the poem.

- Your ability to reorganise information in the poem. For example, you may be asked to summarise key points.

- Your ability to provide information that may not be clearly stated in the extract provided, using what you already know about the text as a whole. This process is called inference. For example, you may be asked to explain how a figure of speech affects your understanding of the poem as a whole.

- Your ability to make your own judgements and form opinions about aspects of the poem. This process is called evaluation. For example, you may be asked if you agree with a statement.

- Your ability to respond to the emotional level of a poem. This is called appreciation. For example, you may be asked what you would have done in the situation described in the poem. You may be asked to discuss how the writer’s style helps to describe the tone and mood of a poem.

Question words

Here are examples of question types found in the exam.

Question type | What you need to do |

Literal: Questions about information that is clearly given in the text or extract from the text | |

Name characters/places/things ... | :Write the specific names of characters, places, etc. |

State the facts/reasons/ideas … | Write down the information without any discussion or comments. |

Give two reasons for/why … | Write two reasons (this means the same as ‘state’). |

Identify the character/reasons/theme … | Write down the character’s name, state the reasons. |

Describe the place/character/what happens when … | Write the main characteristics of something, for example: What does a place look/feel/smell like? Is a particular character kind/rude/ aggressive … |

What does character x do when … | Write what happened – what the character did. |

Why did character x do … | Given reasons for the character’s action according to your knowledge of the plot. |

Who is/did … | Write the name of the character. |

To whom does xx refer … | Write the name of the relevant character/person. |

Reorganisation: Questions that need you to bring together different pieces of information in an organised way. | |

Summarise the main points/ideas … | Write the main points, without a lot of detail. |

Group the common elements … | Join the same things together. |

Give an outline of ….. | Write the main points, without a lot of detail. |

Inference Questions that need you to interpret (make meaning of) the text using information that may not be clearly stated. This process involves thinking about what happened in different parts of the text; looking for clues that tell you more about a character, theme or symbol; and using your own knowledge to help you understand the text. | |

Explain how this idea links with the theme x … | Identify the links to the theme. |

Compare the attitudes/actions of character x with character y … | Point out the similarities and differences. |

What do the words … suggest/reveal about /what does this situation tell you about … | State what you think the meaning is, based on your understanding of the text. |

How does character x react when …. Describe how something affected … State how you know that character x is … | Write down the character’s reaction/ what the character did/felt. |

What did character x mean by the expression … | Explain why the character used those particular words. |

Is the following statement true or false? | Write ‘true’ or ‘false’ next to the question number. You must give a reason for your answer. |

Choose the correct answer to complete the following sentence (multiple choice question). | A list of answers is given, labelled A–D. Write only the letter (A, B, C or D) next to the question number. |

Complete the following sentence by filling in the missing words … | Write the missing word next to the question number. |

Quote a line from the extract to prove your answer. | Write the relevant line of text using the same words and punctuation you see in the extract. Put quotation marks (“ ” inverted commas) around the quote. |

Evaluation Questions that require you to make a judgement based on your knowledge and understanding of the text and your own experience. | |

Discuss your view/a character’s feelings/a theme ... | Consider all the information and reach a conclusion. |

Do you think that … | There is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ answer to these questions, but you must give a reason for your opinion based on information given in the text. |

Do you agree with … | |

In your opinion, what … | |

Give your views on … | |

Appreciation Questions that ask about your emotional response to what happens, the characters and how it is written. | |

How would you feel if you were character x when … | There is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ answer to these questions, but you must give a reason for your opinion based on information given in the text. |

Discuss your response to … | |

Do you feel sorry for … | |

Discuss the use of the writer’s style, diction and figurative language, dialogue … | To answer this type of question, ask yourself: Does the style help me to feel/imagine what is happening/what a character is feeling? Why/why not? Give a reason for your answer. |

Literary features found in poems

| Diction | The poet’s choice of words and how he/she organises them. |

Euphemism | A mild or vague expression in place of a word that is more harsh or direct. |

First person | The poem is written from the point of view of ‘I’ or ‘we’. |

Hyperbole | A deliberate exaggeration. For example, ‘a big’ plate of food is described as ‘a mountainous’ plate of food |

Irony | A statement or situation that has an underlying meaning that is different from the literal meaning. |

Metaphor | A figure of speech that uses one thing to describe another in a figurative way. |

Mood | The emotions felt by the reader when reading the poem. |

Oxymoron | A combination of words with contradictory meanings (meanings which seem to be opposite to each other). For example, ‘an open secret’ |

Personification | Giving human characteristics to non-human beings. |

Pun | A play on words which are identical or similar in sound. It is used to create humour. |

Rhyme | Lines of poetry that end in the same sound. |

Rhythm | A regular and repeated pattern of sounds. |

Sarcasm | An ironic expression which is used to be unkind or to make fun of someone. |

Simile | Comparing one thing directly with another. ‘Like’ or ‘as’ is used to make this comparison. |

Symbol | Something which stands for or represents something else |

Theme | Themes are the main messages of a text. There are usually a few themes in each poem. |

Third person | The poem is written from the point of view of ‘he’, ‘she’ or ‘they’. |

| Tone | The feeling or atmosphere of the poem. |

Sound devices: | |

| Alliteration | A pattern of sounds that includes the repetition of consonant sounds. The repeated sound can be either at the beginning of successive words or inside the word. |

Assonance | The vowel sounds of words that occur close together are repeated. |

Consonance | A sound that occurs at the end of words that are close together is repeated. |

| Onomatopoeia | The use of words to create the sounds being described. |

SONNET 116 BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

Sonnet 116: Let me not to the marriage of true minds was written by William Shakespeare (1564-1616). He lived in England at the time of Queen Elizabeth I and he is one of the most famous English writers. He wrote many plays and over 150 poems. Like this one, most of the poems are sonnets which deal with themes of love, time, and their effect on people and relationships.

1. Themes

The main theme of Sonnet 116 is love. Shakespeare is saying that nothing can stop true love and that it never changes, no matter what happens in life. True love can survive even during life’s problems and can guide you through difficult times. Not even time can destroy true love, which lasts forever.

The poet is so sure of what true love is that he says that, if he is wrong, then he has never written anything, including this poem! This is how he concludes his argument that true love is constant and everlasting.

Note: This poem is written in Elizabethan English. The glossary after the poem gives the deunitiono of Elizabethan words.

Definitions of words from the poem: | ||

Line 1: | let me not | don’t allow me to |

marriage | union, unity, bond | |

Line 2: | admit impediments | allow obstacles, flaws or anything else to get in the way |

Line 3: | alters | changes |

alteration | a change | |

Line 4: | remover | person taking (love) away; |

to remove | to take away | |

Line 5: | ever-fixèd mark | permanent, unchanging marker |

Line 6: | tempests | storms, challenges |

shaken | moved | |

Line 7: | wand’ring bark | ship lost at sea |

Line 8: | worth | value |

taken | measured | |

Line 9: | fool | servant |

Line 10: | sickle | a tool used to cut grass; |

compass | range; direction | |

Line 11: | brief | short |

Line 12: | bears it out | makes it last |

edge of doom | end of the world; end of time; death | |

Line 13: | error | mistake |

Line 14: | writ | wrote |

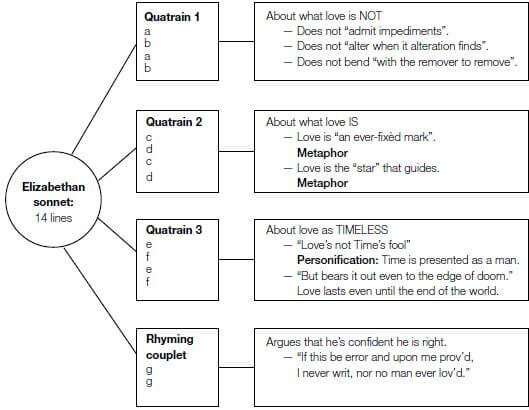

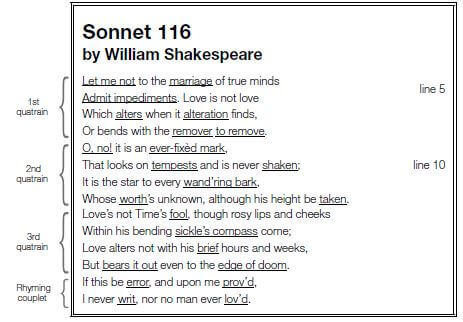

2. Type and form

Sonnet 116 is an Elizabethan sonnet. It has 14 lines in one verse that is made up of:

- Three quatrains of four lines each; and

- A rhyming couplet of two lines at the end of the poem.

The rhyming scheme for Sonnet 116 is abab cdcd efef gg

Rhyme: Words at the end of the lines which have the same sound such as "minds" and "finds".

3. Analysis

First quatrain (lines 1 – 4) Let me not to the marriage of true minds |

In the first quatrain, the poet suggests what love is not. Nothing should get in the way (“impediments”) of people who are united (perhaps by love or marriage) and have the same values (“true minds”). People who have true minds share the same beliefs, values and ideas. They may be close friends or family members, not only lovers or people who are married in an official way.

Note: Marriage can also mean a closeness or union between two people who love each other.

He celebrates this kind of love and explains that true love does not change (“alters”) when circumstances change (“it alteration finds”). True love stays constant (steady or even) and stable and it does not weaken (“bend”) when there are difficult times, or the loved one does not seem to love any more.

The poet emphasises that love which changes or weakens is not true love by repeating “alter” and “alteration”; and “remover” and “remove” - these words suggest things that take love away or change love.

Note: Notice how "work" amd "bark" rhyme as do "shaken" and "taken".

Second quatrain (lines 5 – 8) O, no! it is an ever-fixèd mark |

In this quatrain, the poet suggest what love is. The poet explains that he thinks the love of true minds is stable and permanent. His exclamation, “O, no!” indicates how strongly the poet rejects the idea that anything can change true love. The poet then uses metaphors based on ships and sailing to tell us what love really is.

In the first metaphor the poet says that true love is an “ever-fixèd mark”, perhaps like a lighthouse. It stays shining and constant as a guide even during the worst storms (“tempests”). This metaphor tells us that true love is faithful and steady and will help you to manage even the worst of life’s problems.

In the second metaphor, Shakespeare says that true love is the “star” that guides a ship that has gone off course or got lost (“wand’ring bark”). This star refers to the North Star, which was used by a ship’s captain to steer a ship in the right direction as it is a constant star, always in the same place in the sky. He is saying that true love is constant and never changes its nature. It can be trusted to guide you through life, like the North Star guides a “wand’ring bark” or a ship lost at sea.

Shakespeare also says that, although the position of a star can be measured, we cannot know the worth or value of the star. In the same way, the value of true love is something which cannot be measured, so its worth is “unknown” (line 8), although it can give us direction and meaning in life.

Did you know: In Shakespear's day, sailing ships were made of wood. The captain steered the ship by measuring the position of the stars to guide the ship across the sea.

Third quatrain (lines 9 – 12) Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks |

In the third quatrain, the poet tells us that such love is timeless – it cannot be measured and lasts to the end of the world.

The passing of time has no effect on true love. The use of a capital letter in “Time” tells us that this is personification, that Time is a person. Shakespeare is writing about time as if it is a man, so he writes “his” not “its”.

However, the speaker in the poem says that love is not the “fool” of Time. He says that love is not a servant that has to obey Time’s rules and so, although Time destroys youth and beauty (cuts down “rosy lips and cheeks” with his “sickle”), love does not change. The poet says that love will last forever, even until the end of the world (“the edge of doom”).

Did you know: Father Time is also called the Grim Reaper or Death. He carries a sickle to harvest people, as a farm worker cuts grass with a sickle. He destroys our youth and beauty so that we get old and wrinkled.

Rhyming couplet (lines 13 – 14) If this be error and upon me prov’d, |

After telling us that love does not change (first quatrain), that love gives us guidance (second quatrain) and finally that love never ends (third quatrain), the poet ends the poem with a little joke. He says that if anyone can prove that his views of love are wrong then it would mean that he didn’t write anything and that no one has ever loved anyone.

This is a clever argument to end the poem with because we all know that Shakespeare has written – we are studying one of his poems right now – and of course people have loved before, and so what he says about love must be correct.

4. Tone and mood

The tone of the poem is generally confident. Shakespeare believes so strongly in love that he does not say love is “like” anything (a simile). Instead, he uses metaphors to say that love IS that thing: love IS a “star” and love IS an “ever-fixèd mark”.

In the third quatrain, Shakespeare’s tone is scornful of Time’s “brief hours and weeks” because true love is not affected by time. Time passes and we grow old and die but love does not die.

The tone of the rhyming couplet is persuasive. The poet or speaker wants to persuade the reader to agree with his views about true love.

The mood of a poem is how it makes the reader feel. How does this poem make you feel? For example, happy, sad, angry, or indifferent?

Note: Scournful is an expression of digust towards someone or something that is seen as unworthy.

Also have you noticed that there are no similies in this poem, only metaphors?

Summary

Sonnet 116 : Let me not to the marriage of true minds by William Shakespeare

- Theme

- Love is constant and everlasting.

- Love is constant and everlasting.

- Type and form

- Tone and mood

- Tone: Confident, scornful, persuasive

- Mood: How does this poem make you feel? Happy, sad, angry or indifferent? Always give reasons for your answer.

Activity 1

Refer to the poem on page 2 and answer the questions below.

- Complete the following sentence by using the words provided in the list below.

This is a typical (1.1) ... sonnet because of the three (1.2) ... and the (1.3) ... that rhymes. (3)Petrarchan; sestet; Elizabethan; Couplet; quatrains; octave - Quote a word in the first line which has connotations of love and unity. (1)

- Refer to the following words in line 1 (“... the marriage of true minds”).

To what do these words refer? (2) - Refer to lines 2-4 (“Love is not love ... remover to remove”).

Using your own words, explain the meaning of these lines. (2) - Choose the correct answer to complete the following In line 5, the words “O, no ...” show that the speaker is ...

- uncertain.

- arrogant.

- doubtful.

- convinced. (1)

- Refer to line 7 (“It is the star to every wand’ring bark”).

Give the literal meaning of the underlined words. (1) - Is the following statement TRUE or FALSE? Quote THREE consecutive words to support your answer.

It is impossible to measure the value of love. (2) - Refer to the following words in line 9 (“Love’s not Time’s fool”). Identify the figure of speech used (1)

- Refer to lines 13 and 14 (“If this be ... man ever loved”).

How does the poet use the last two lines to make his argument on true love convincing? (2) - Do you agree with the speaker’s view of love? Explain your (2) [17]

Note:

- Connotations - words with meanings linked to a key word. For example, the connotations of "morning" are fresh,new,early.

- Consecutive words - words that directly follow after one another.

Answers to Activity 1

|

Hint ; In question 7, one mark will be given if the first part of the answer (true) is correct. To get 2 marks, give the correct answer and quote the correct three words.

Note: When a question asks for your own view or opinion, you must say if you agree or not and then give a reason for your viewpoint to get 2 marks.

DEATH BE NOT PROUD BY JOHN DONNE

This poem was written by John Donne (1572-1631) who lived at the same time as Shakespeare. Donne had an adventurous early life. He travelled by sailing ship on two expeditions to the New World (the United States). He also ran away with his employer’s 16-year-old niece, Anne, whom he married, and so he was fired from his job. Donne was a Christian and became an Anglican priest and later the Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral in London.

1. Themes

The theme of this poem is death. The poet speaks directly to Death, in person, and tells Death not to think that he is important and powerful because Death is really just a kind of sleep – and rest and sleep are pleasant. We all wake from sleep: even people who die will wake from death – in heaven! The poet points out that actually death brings us benefits and that it has no power. There is therefore no reason for people to be afraid of death.

This poem is based on the Christian paradox that in order to live forever you have to die. In the Christian belief, physical death is the gateway to eternal or everlasting life in heaven.

The poet makes a clever argument in this poem. His idea is set out like this:

- When we die, it looks as if we are asleep.

- When we sleep, we will eventually wake up.

- If death looks like sleep, then we will also wake up from death.

- If we wake up from death, we cannot be dead.

- Death is destroyed by eternal life.

Vocab: A paradox is a statement made of two opposite ideas that seems to make no sense but may be true.

Definitions of words from the poem: | ||

Line 1: | thee | you |

Line 2: | mighty | powerful, strong |

dreadful | terrifying, tragic | |

art | are | |

Line 3: | thinks’t | think |

dost | does | |

overthrow | destroy | |

Line 4: | canst | can |

Line 5: | pictures | copies, images, representations, likenesses |

Line 6: | flow | come |

Line 8: | souls’ delivery | souls going to heaven, to God |

Line 9: | Fate | luck |

chance | accidents | |

Line 10: | dwell | live |

Line 11: | poppy | drug |

charms | magic spells | |

as well | just as well | |

Line 12: | stroke | attack |

swell’st | swell, grow big | |

Line 13: | sleep | death |

wake eternally | live forever | |

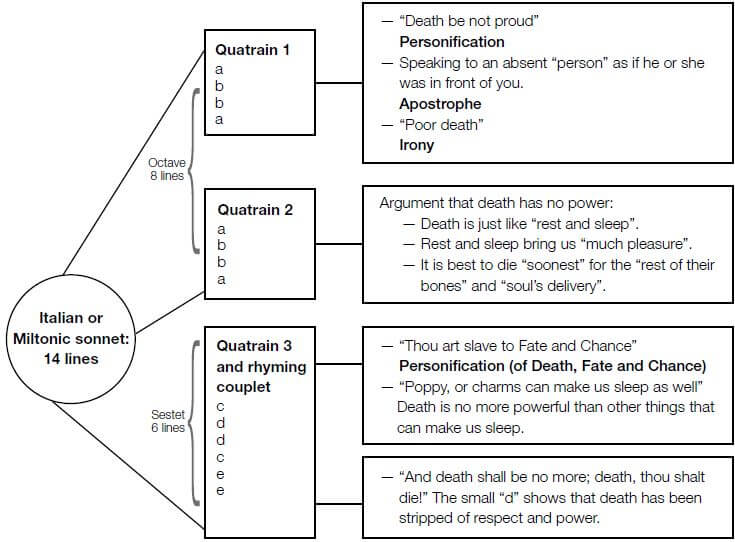

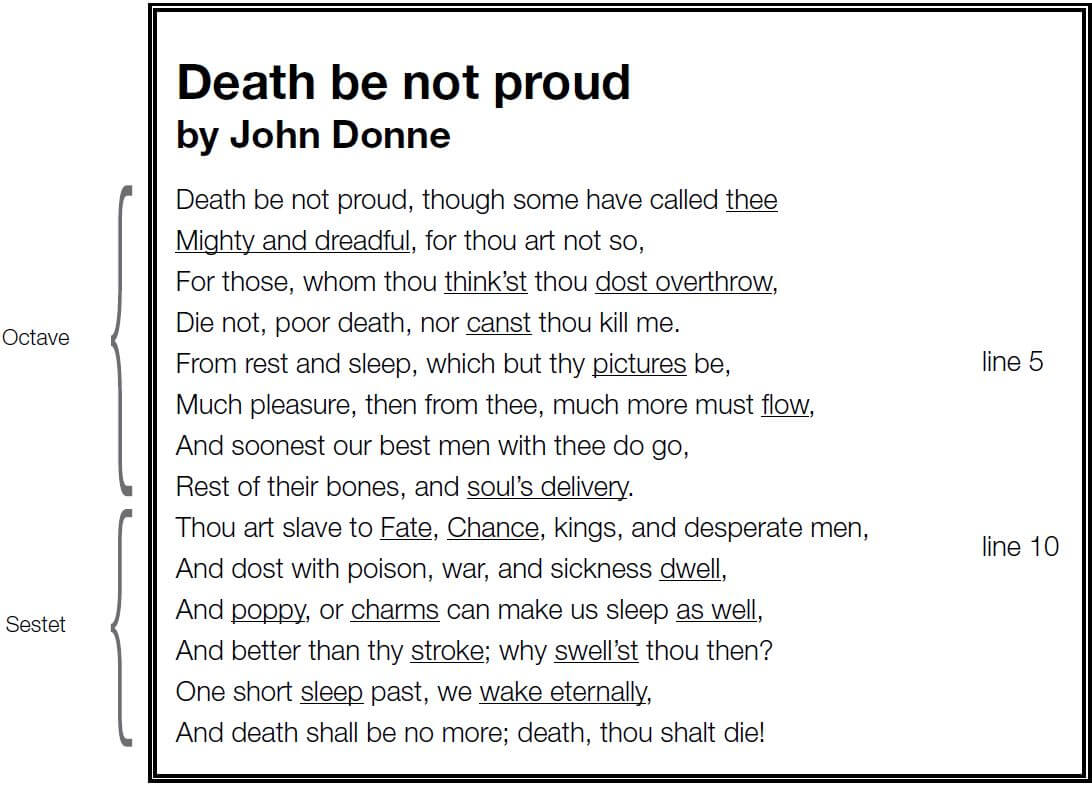

2. Type and form

The poem is an Italian or Miltonic sonnet. This is because its 14 lines are made up of:

- An octave of eight lines made up of two quatrains; and

- A sestet of six The sestet is made up of one quatrain and arhyming couplet at the end of the poem.

The rhyming scheme in this sonnet is abba abba cddc ee.

Hint: "Octo" (in octave) means eight "ses" means six, so a sestet has six lines

3. Analysis

First quatrain of the octave (lines 1 – 4) Death be not proud, though some have called thee |

The speaker talks to Death as if Death was a person. This is a figure of speech called personification. By personifying Death, and giving it a human quality – pride – the poet makes death less scary. Death then only has the same power as people like you and me.

The speaker is using another figure of speech here called apostrophe – no, not the punctuation mark! Apostrophe is when you speak directly to an absent person or thing as if he or she was standing in front of you.

The poet orders Death not to be “proud” (arrogant) because people do not really get defeated (“overthrown”) by Death. In fact, Death cannot kill anyone – not even the speaker. The poet explains in the rest of the poem why Death cannot really “kill” anyone.

The poet, however, says that only “some” people consider death “mighty and dreadful” (line 2). In line 3, he goes on to tell Death that people it thinks it has destroyed do not die, and Death cannot kill him, the poet. He mocks Death by pretending to be feel sorry for Death, calling it “poor death”.

The poet is using the word “poor” in an ironical way here, as he does not really pity death.

Vocab: Poor can mean financially poor; or someone undeserving pity. In this poem, the word "poor" is used scornfully. The poet does not really pity death.

Also: Note how the rhyme scheme here is abba. " Be" rhymes with "delivery" and "flow" with "go".

Second quatrain of the octave (lines 5 – 8) From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be, |

People who die look like they are resting and sleeping – both rest and sleep are enjoyable (they give us “much pleasure”). Death is just a copy of these pleasant experiences.

The poet continues to mock Death by saying that if sleep is great and death is like a big sleep – then what an even greater pleasure death must be. Even more, the quicker people die, the better for them (“soonest our best men with thee do go” in line 7)!

The poet gives his evidence for this in lines 7 and 8, where he says the “best men”, those with true faith, welcome death because it rests their bodies (“bones”) and delivers their souls to God.

Third quatrain (sestet and rhyming couplet, lines 9 – 14 Thou art slave to Fate, Chance, kings, and desperate men, 10 |

Note: The rhyme in the sestet is cddc ee

The speaker continues to criticise Death. He says that Death does not have the power to kill people on his own. Death is a servant (a “slave”) to many horrible “masters” such as destiny (“Fate”) and accidents (“Chance”), which may kill us. Death also works for “desperate men” – this would be men who may rob and murder. Death also has to live (“dwell”) with very nasty companions that will do the actual killing: “poison, war, and sickness” (line 10).

Hint: Connotation of a word are extra meanings or the associations with that word. By using the word "Slave", the poet is saying that Death is not free and has no control over his life.

The poet personifies Death as a slave who has no freedom to act on his own. He is used by other forces which cause death. The poet uses capital letters (F and C) for Fate and Chance as if they are important people; and Death is their slave.

In line 12, the poet reminds Death that even simple sleeping drugs (opium, made from the “poppy”) and charms (“magic”) can make us “sleep” better than Death can (“…better than thy stroke”). The poet asks: if these things do the same work as Death, why is Death is so full of self-importance, “why swell’st thou then?” There is an expression “swell with pride” that describes the feeling of being filled with pride, which gives us an image of a proud, arrogant person pushing his chest out to look big and important! The poet suggests that Death has nothing to be proud of.

Rhyming couplet (lines 13 – 14) One short sleep past, we wake eternally, |

The last two lines of the poem are a rhyming couplet. Although the words “eternally” and “die” do not seem to rhyme – they would have rhymed in the English accent of that time.

Notice that now the speaker uses a small “d” for death in the last line of the poem (line 14). Death is not important anymore and does not get the capital “D” of a proper noun.

4. Tone and mood

The poet’s tone in the poem is scornful and mocking in the way that he gives orders to Death, which is often considered a terrifying mystery. The tone is also critical of death.

In the end, the speaker uses a triumphant tone because he has won a victory over Death, as Death is conquered and destroyed by eternal life.

The mood of a poem is how it makes the reader feel. How does this poem make you feel? For example, happy, sad, angry, or indifferent.

Summary

Death be not proud by John Donne

- Theme

Death is not a terrifying mystery, but a force without real power. - Type and form

- Tone and mood

- Tone: Scornful, mocking, triumphant

- Mood: How does this poem make you feel? Happy, sad, angry or indifferent? Always give reasons for your answer.

Activity 2

Refer to the poem on page 10 and answer the questions below.

- Refer to the following words in line 1 (“Death be not proud”):

Identify the figure of speech used (1) - Explain why the poet has used this figure of (2)

Hint: to explain this figure of speech, think of how and why the poet talks to Death as a person. - Which three words from the list below could be used to describe Death? (3)

arrogant; clever; proud; friendly; over-confident; loving - Is the following statement TRUE or FALSE?

Everyone fears Death.

Quote ONE word from the poem to support your answer. (2)

note: Write down either true or false and then your one word answer. Remember that this is a quote so make sure you spell the word exactly as it is in the poem. - Complete the following sentences by using the words provided in the list Write down only the words next to the question number.

The poet says that “rest and sleep” are “pictures” of Death, meaning they only (5.1) ... like death. However, people rest and sleep for (5.2) ... (2)entertainment; temporary; relaxation; end; look; final - Using your own words, write down THREE causes of death statedin the poem. (3)

- Refer to the following words in line 12 (“why swell’st thou then?”) Explain the meaning of these words as they are used in the (1)

- Refer to lines 10-14. Name two things which have the sameeffect as Death. (2)

- Write down the correct tone word in brackets for each of the lines below:

- “Death be not proud for, thou art not so” (lines 1- 2) (triumphant/critical/ mocking)

- “Thou art slave to Fate, Chance, kings, and desperate men” (line 9) (triumphant/critical/mocking)

- “And poppy, or charms can make us sleep as well, And better than thy stroke” (lines 11-12)

(triumphant / critical / mocking) - Death, thou shalt die.” (line 14) (triumphant/critical/mocking) (4)

- In the last two lines (13–14) the speaker’s tone is ...

- triumphant and victorious

- submissive and angry.

- sad and disappointed.

- thoughtful and fearful. (1)

- Discuss the message the poem has for its (2) [23]

To get 2 marks, you must give 2 points.

Answers to Activity 2

- Personification OR apostrophe ✓ (1)

- Personification: The poet gives Death human qualities in order to mock/poke fun at/ridicule/laugh at Death/ to show that Death is like an ordinary human/mortal/ not powerful ✓✓

OR

Apostrophe: He addresses Death as if Death is present/ in front of him. ✓✓ (2) - arrogant ✓/proud ✓/over-confident ✓ (3)

- False. “some” ✓✓ (2)

- 5.1 look ✓ (1)

5.2 relaxation ✓ (1) -

- You are destined to die in a certain way (Fate). ✓

- You can die in an accident (Chance). ✓

- Your death can be ordered by kings/powerful people. ✓

- You can die in a war. ✓

- You can be murdered. ✓

- You can kill yourself/ suicide. ✓

- You can die by taking poison. ✓

- You can die from illness/disease. ✓ (3)

- The poet is questioning/asking why Death is filled with pride/proud/OR why Death is arrogant/pompous/haughty/ swollen with pride. ✓ (1)

- “poppy” ✓ and “charms” ✓ (2)

-

- critical ✓

- critical ✓

- mocking ✓

- triumphant ✓ (4)

- A / triumphant and victorious ✓ (1)

-

- You should not be afraid to die. ✓

- Death has no power. ✓

- Death is temporary/does not last forever. ✓

- There is life after death. ✓ (2) [23]

NOTE:

- In question 4, a mark is awarded only if both parts of the answer are correct: False and "some".

- Any three of the answers in question 6 are acceptable

- Any 2 of the answers n question11 are acceptable

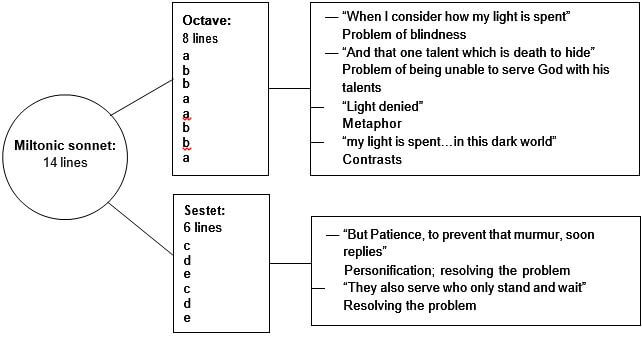

AN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL CLASSROOM IN A SLUM BY STEPHEN SPENDER

This poem was written by Stephen Spender (1909-1995). He was a modern English poet and writer.

Much of his writing is about human rights and social justice. He was politically left-wing and was a member of the Communist Party in Britain in the 1930s. He was actively involved in the anti-Nazi and anti-Fascist politics of that time.

Later in life he edited literary magazines and taught at many institutions. He became Professor of English at University College in London in the 1970s.

1. Themes

The two main themes are a protest against social inequality and againstpoor quality education.

The poet describes some children in a classroom in a very poor area. Most of them look unhealthy and unhappy. The pictures on the walls of the gloomy classroom show an interesting world outside the slum, but the children are trapped in a world of poverty and may never experience a better life unless something is done to change their future.

The poet calls upon the people responsible for education to free these children from their poverty and give them the opportunity to live a better life.

VOCAB: In the title of the poem, an 'elementary school' is a primary school (grade 1-7). A 'slum' is a very poor area of a city or town with few facilities or services.

An elementary school classroom in a slum by Stephen Spender

Stanza1 | Far far from gusty waves, these children’s faces. | 1

|

Stanza 2 | On sour cream walls, donations. Shakespeare’s head, |

10

15 |

Stanza 3 | Surely, Shakespeare is wicked, the map a bad example |

20 |

Stanza 4 | Unless, governor, teacher, inspector, visitor, | 25

30 |

Words to know:

Definitions of words from the poem: | ||

Stanza 1 | ||

Line 1: | gusty | windy |

Line 2: | weeds | unwanted plants |

pallor | pale, unhealthy skin colour | |

Line 4: | stunted | undeveloped |

heir | receiver | |

Line 5: | reciting | repeating |

gnarled | twisted, crooked | |

Line 6: | dim | almost dark, badly lit |

Line 7: | unnoted | unnoticed |

Line 8: | squirrel | small, tree-climbing animal |

Stanza 2 | ||

Line 9: | donations | gifts (usually for charity) |

Line 10: | dawn | sunrise |

dome | curved shape; Shakespeare’s head | |

Line 11: | Tyrolese | Austrian tyrol (mountains) |

open-handed | generous | |

Line 12: | awarding | giving |

Line 14: | sealed | closed up |

lead | dull, grey | |

Line 15: | capes | land going out into the sea |

Stanza 3 | ||

Line 19: | slyly | secretly, sneakily |

cramped | small, crowded | |

Line 20: | fog | thick mist |

slag heap | coal mine dump | |

Line 21: | peeped | looked shyly |

Line 22: | blot | mark |

doom | bad future | |

Stanza 4 | ||

Line 25: | governor, inspector | people in charge of running schools |

Line 27: | catacombs | underground burial chambers for the dead |

Line 30: | azure | bright blue |

Line 31: | white leaves | books |

green leaves | nature | |

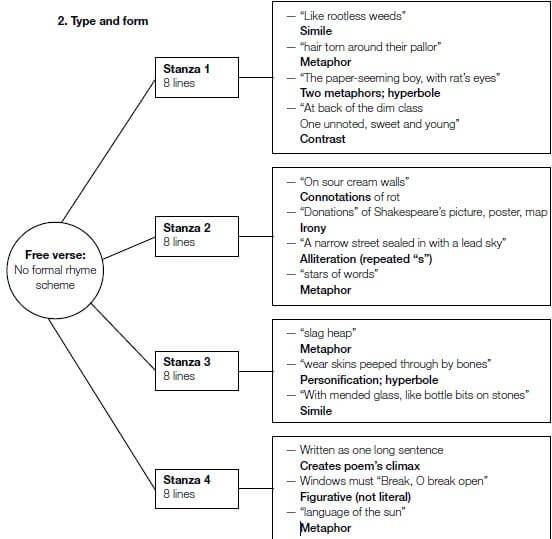

2. Type and form

This poem is divided into four stanzas of eight lines each. It is written in an informal style with no words that rhyme at the ends of the lines, which is typical of modern poetry.

This is known as free verse.

3. Analysis

Stanza 1 (lines 1 – 8) Far far from gusty waves, these children’s faces. |

Note: Rhyming lines of poetry end in words that sound the same.

In stanza 1, the poet describes some of the children in the classroom. The opening lines of the poem are not complete sentences and have an unusual word order:

Far far from gusty waves these children’s faces

Like rootless weeds, the hair torn round their pallor. (lines 1 and 2)

In ordinary English, the first two lines would be written: “These children’s faces are far, far from gusty waves and they look like rootless weeds. ” By changing the word order, the poet repeats “Far far” to start the poem. This emphasises the poet’s frustration about how far the children’s environment is from what it should be. His tone is angry. The words “gusty waves” (line 1) suggest wind and sea – a healthy, fresh and beautiful place, unlike the gloomy slum they are living in.

In a simile, the poet compares the children to “rootless weeds” (line 2). Weeds are small, unwanted plants. The word “rootless” gives us an even more powerful image of how weak the children are: plants cannot grow without roots to take in water and nutrients, and without roots, they do not even seem to belong in one place in the ground. The simile “like rootless weeds” suggests these children are thin, weak and underfed, but also that they do not have a place in the world. The children’s “pallor” (line 2) makes them look pale and sickly, while the metaphor “torn hair” (line 2) suggests that their hair is messy and they are not well cared for.

The poet goes on to describe some of the children in the class. One girl is tall for her class, but instead of standing tall and proud, she hangs her head (“weighed-down head” in line 3). This suggests she is thin and her head feels too heavy for her body, or that she feels depressed and is not concentrating on the lesson. A boy is “paper-seeming” (line 3 and 4). This metaphor suggests that he is as pale and thin as a piece of white paper. The poet uses hyperbole here to emphasise how thin the boy is.

The metaphor “rat’s eyes” (line 4) paints a picture of little eyes moving quickly around, like a rat’s – perhaps always looking for danger or a way to survive. Some rats have red eyes, so perhaps the boy has an eye disease, or has been crying. The image of this boy is of a thin, pale, frightened, unhealthy child.

A third boy suffers from a disease he has inherited from his father that has left him undeveloped (“stunted”) with “twisted bones” (line 5). To “recite” is to repeat something and learn it off by heart. The poet uses irony by saying the boy “recites” his “disease”, instead of his schoolwork. The poet could be suggesting that the child will repeat the disease by passing it on to his own children one day. The emphasis is on the repetition of disease and ill health.

We are also given the impression that the children are taught to learn things off by heart, without really understanding what they are learning about.

In the final three lines of this stanza, the poet introduces a contrast. The last child mentioned, sitting at the back of the dull, poorly-lit room, is different from the others and looks younger than they do. “Sweet and young” (line 7) suggests he is innocent and has not yet been as badly affected by slum life as the other children and still has dreams of something better. Instead of listening to the lesson, he is dreaming of playing in a different place, somewhere outside in nature (“tree room”). A squirrel is a little animal with bright eyes and a bushy tail that runs freely up and down trees. The child perhaps imagines playing as freely as a squirrel in a beautiful place.

Note:

- A simile is a direct comparison between two things using 'like' or 'as'

- Hyperbole: An overstatement used for emphasis. Here, the boy is not really as thin as a piece of paper.

- A metaphor is a way of comparing two things without using the words 'like' or 'as'.

Stanza 2 (lines 9 – 15) On sour cream walls, donations. Shakespeare’s head, |

In the second stanza, the poet describes the classroom. The colour of the classroom walls is “sour cream” (line 9). The connotations of this are of cream that has gone bad, which suggests the walls are dull and not very clean.

The walls are decorated with what the poet calls “donations” (line 9) – which are gifts to the school, but these gifts may not improve the children’s lives. Ironically, these gifts suggest a world that the children may never be able to experience because of their poverty. The speaker uses a bitter tone when he tells us that these children have a life which is a contrast to these pictures. Their world is dirty, polluted, grey and without much freedom.

Note:

- Imagine some connotations of 'sour cream'. They may include 'rotten', 'horrible tatse' or ' old'.

- Irony: A statement with an underlying meaning different from its surface meaning.

Look at what is on the walls and note the irony of these “donations”:

- A picture of Shakespeare: he represents the world of culture, of theatres and plays that, ironically, the children may never see. The phrase “cloudless at dawn” (line 10) suggests a new day, a new life, and contrasts with the grey skies of the slum outside the classroom “Civilised dome” (line 10) may refer to Shakespeare’s bald head in the shape of a dome. It could also refer to buildings with domes in cities that suggest other cultures and faraway places.

- A poster of the Tyrol: The Tyrolean mountains in Austria have beautiful valleys that are green and filled with wild flowers in summer. Cows graze and wear bells around their Many tourists travel there on holiday, but these children may never get a chance to do that.

- A map of the world: This seems “open-handed” (generous), as if it offers the children the whole, exciting world with its wonderful opportunities, but most of them may never leave the slum in which they live.

The poet’s tone is sad when he says, “these windows, not this world, are world” (line 13). “These windows” refer to the classroom windows that look out on the slum. They do not look out on “this world”, which is the wonderful world shown in the pictures and the map. Instead, the windows “are [their] world”; in other words, the children’s world is the slum that they see through the windows.

The speaker goes on to describe the slum outside the classroom and what it means for the lives of the children. The “narrow” street suggests that the area is built up and crowded. It is “sealed” (line 15) or closed in by the grey, cloudy, heavy (“lead”) sky. The words “lead”, which is a heavy grey metal, and “sealed” make it seem almost as if the children are trapped in a lead coffin. The alliteration of the “s” sound that links the words “street/sealed/ sky” adds to the trapped, closed-in feeling.

As he did at the start of the poem, the poet uses the repetition, “Far far ...” (line 16) to emphasise how the children are cut off from nature and the beautiful world beyond the slum. The metaphor “stars of words” (line 16) is interesting. The stars are beautiful and represent dreams, great ambitions and things that are bright and fine. “Stars of words”, therefore, make us think not only of a beautiful night sky, but also of the wonderful ways words can be used: words express wisdom and knowledge, they can inspire us, they can empower us. But perhaps these children have no experience of words used in this way.

Notice that in this stanza, the word “world” is repeated four times, each time with a slightly different meaning or connotation.

Stanza 3 (lines 17 – 24) Surely, Shakespeare is wicked, the map a bad example |

In this stanza, the poet uses an indignant tone. His anger about injustice increases when he thinks about the children’s future.

“Wicked” (line 17) seems a very strange word to use to describe a great and inspiring writer like Shakespeare, and how, we may wonder, can a map be “a bad example” (line 17) ? We are answered in the next line. Great art and literature, maps of the world, together with a life of travel and adventure (ships) in warm, sunny places belong to a life these children may never have – unless they turn to crime to escape from their poverty. The poet’s diction (his choice of words, such as “wicked/bad”) and the strong rhythm of these lines show how strongly he feels. The poet’s unhappiness is shown again in the next two lines when he describes what the future holds for these children. Their homes are “cramped holes” (line 19) and their lives are dull (“fog”) and without a bright future (“endless night”).

Lines 20 to 24 paint a tragic picture of the children’s future. If you have ever seen a place where coal is mined, you will have seen the slag heaps which are huge dumps of black waste from the coal mines. The children in the poem do not literally live on a slag heap (although their slum may be close to one) but this strong metaphor tells us that their lives are not pleasant, and are without joy or hope.

The poet uses personification in “wear skins peeped through by bones” (line 20) to emphasise how thin the children are. Their bones are “peeping” or looking through their skin. This is also an example of hyperbole as the bones would not actually be sticking out through the skin. The children who wear the broken glasses cannot even see properly – “With mended glass, like bottle bits on stones” (line 21). This simile may refer to the children’s future as well as their physical condition. Is the future they see ahead of them as broken as their glasses? They have nothing good to look forward to as “All their time and space are foggy slum” (line 23).

The last line of stanza 3 shows how angry the poet feels about the future to which these children are condemned. He speaks in a direct, angry andaccusing tone to us and all those people in authority. He says that we may as well condemn the children to endless unhappiness and paint the “map” of their future with a picture of a huge slum, “as big as doom” (line 24).

You met the word “doom” in the Shakespeare sonnet, when it meant 0the end of time/the world, the Day of Judgement. Here “doom” has the connotation of being condemned to suffering and death from which there is no escape. Notice the rhythm of this line, with five short, strong, heavy words following one another, almost like beats of a drum - “So blot their maps with slums as big as doom”.

Note:

- Read this line out loud and hear how it expresses the poet's anger. ' So blot their maps with slums as big as doom'.

Stanza 4 (lines 25 – 32) Unless, governor, teacher, inspector, visitor, |

In the last stanza, the poet introduces hope to a hopeless situation. He calls on those in authority to change these children’s lives and give them a better future. He calls on the school governor (many South African schools have governing bodies), teachers, school inspectors and visitors to take action. To express his excited tone about what he wants to happen, the poet has written this stanza as one long sentence that builds to a climax. However, to make it easier to discuss, it will be divided into two.

Unless, governor, teacher, inspector, visitor, 25

This map becomes their window and these windows

That shut upon their lives like catacombs,

Break O break open, till they break the town

Note: The poet does not mean the authorities must literally break the windows. He means they must Uguratively help to open up the children's minds and lives.

The first word, “Unless” (line 25), offers the authorities an alternative to “blot[ting] their maps with slums as big as doom”. Instead, the “map” on the classroom wall should no longer be a “temptation” to steal, but become an offer of real opportunities for the children. It should be a “window” (line 26) to all the world has to offer. The authorities must, figuratively, break open the windows for the children and offer them a different future.

At present they are imprisoned as if they were in a grave (“catacomb”). The poet emphasises the need to free the children from this future by his urgent tone. He repeats “break o break” (line 28) and the excited exclamation “o”; he wants the children to be able to escape their dull and lifeless future and even the town itself.

And show the children to green fields and make their world

Run azure on gold sands, and let their tongues 30

Run naked into books, the white and green leaves open

History theirs whose language is the sun.

In the last four lines, the poet’s tone is a passionate plea for the authorities to give the children a different life and a better environment. He wants them to enjoy the green countryside and nature, to play freely and explore the sea and the beach (“run azure on gold sands”) – in other words, they need to experience an unlimited world. He wants them to discover the joy of reading books, which are a source of knowledge, delight and wisdom. He uses the metaphor “their tongues run naked” (line 30 and 31), which suggests drinking up the contents of books the way we drink water if we are thirsty.

The poet wants them to show the same enthusiasm for books and knowledge that are relevant and make sense to them. Here the poet makes it clear that it is only through a good education and a better environment that the children will have the opportunities that at present they do not have. He wants them to have access to “white” leaves (a leaf also means a page, so white leaves are the pages of books) and “green leaves” (nature, the wider world) so that they will have a different future.

The poem reaches its climax in the last line with a powerful metaphor: the new “history” of their lives should be written in the “language of the sun” (line 32). The sun is the source of life, warmth, brightness, energy. These are the qualities that should be part of these children’s lives.

Contrasts |

4. Tone and mood

In stanza 1, the tone is angry and frustrated because of the hardship the children face.

In stanza 2, the speaker uses a bitter and sad tone when he contrasts the pictures on the classroom wall with the hard realities the children face.

In stanza 3, the tone is indignant and accusing about the injustice the children face in the future.

In stanza 4, the tone is excited and urgent about the need to improve the children’s situation. The final tone is a passionate plea to do so.

The mood of a poem is how it makes the reader feel. How does this poem make you feel? For example, happy, sad, angry, or indifferent.

Summary

An elementary school classroom in a slum by Stephen Spender

1. Theme

A prootest against social inequality and against poor quality education

2. Type and form

3. Tone and mood

Tone: Moves from angry, frustrated, bitter, sad, indignant and accusing; to excited, urgent and passionate.

Mood: How does this poem make you feel? Happy, sad, angry or indifferent? Always give reasons for your answer.

Activity 3

Refer to the poem on page 19 and answer the questions below.

- Complete the following sentences by using the words provided in the list Write down only the words next to the question number (1 - 3).

The setting (background) of the poem is a (1) ... school in a (2) ... area. There are very few (3) ... in the classroom. (3)good; primary; children; resources; high; poor - Using your own words, describe the children in the classroom

State THREE points. (3)

NOTE: in this question use your own words. Do not quote directly from the poem. For 3 marks, give 3 points. - Refer to lines 6-8.

In your OWN words, say how this child is different from the rest of the children in his class. (1) - Refer to stanza

How does the speaker feel about the “donations”? Give a reason for your answer. (2)

Note: When you are asked to give a reason, the reason must be based on the poem. - Refer to line 15 (“A narrow street sealed in with a lead sky”).

5.1 Identify the figure of speech used (1)

5.2 Explain why the poet has used this figure of (2) - Refer to stanza

Is the following statement TRUE or FALSE? Quote TWO consecutive words to support your answer.

The children’s homes are large and comfortable. (2) - Choose the correct answer to complete the following sentence: In stanza 4, the speaker’s tone shows that he is ...

- commenting critically.

- pleading passionately.

- complaining bitterly.

- demanding forcefully. (1)

- Refer to stanza

Name ONE experience the speaker wishes the children to have. (1) - In your view, how does the speaker (poet) feel about the children? Using your OWN words, give TWO reasons for your (3) [19]

Note: When asked for your view, the answer requires your emotional response and understanding of the poem. For 3 marks, make 1 point about the speaker,s feeling (1 mark) and then give 2 reasons (2 marks).

Answers to Activity 3

|

AUTO WRECK BY KARL SHAPIRO

Auto wreck was written by Karl Shapiro (1913-2000). He was an American poet who began writing poetry when he was fighting in the Second World War (1939 - 1945). He sent his poems back to America, where his fiancée had them published. He wrote Auto wreck in 1941, during the war.

He is famous for writing poetry about ordinary things such as flies, cars, supermarkets and this car crash. Shapiro was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1945 and was the American Poet Laureate in 1946 and 1947.

Note

- An 'auto-wreck' is how Americans refer to a acar-crash.

1. Themes

The main theme of the poem is death, and the uncertainty of life.

The poem shows how uncertain and insecure life can be. None of us knows when and how we will die. The people in the cars were probably not thinking at all about life and death when suddenly the crash happened. In a moment, their lives have been changed by horrible injuries, or have been taken away altogether. The poet has no reasonable explanation for this.

Auto wreck by Karl Shapiro

Stanza 1 | Its quick soft silver bell beating, beating, |

5 |

Stanza 2 | The doors leap open, emptying light; |

10 |

Stanza 3 | We are deranged, walking among the cops | 15

20 |

Stanza 4 | Our throats were tight as tourniquets, | 25 |

30 | ||

Stanza 5 | Already old, the question Who shall die? |

35 |

Words to know:

Definitions of words from the poem: | ||

Stanza 1 (lines 1 – 14) | ||

Line 2: | ruby | red |

flare | bright light warning of danger | |

Line 3: | pulsing | throbbing |

artery | main blood vessel | |

Line 5: | beacons | lighted signs or traffic lights |

illuminated | lit up | |

Line 9: | stretchers | beds for carrying the injured |

mangled | badly injured | |

Line 10: | stowed | packed away |

little hospital | ambulance | |

Line 11: | hush | quiet |

tolls | sound a bell makes | |

Line 12: | cargo | load of victims of the crash |

Line 14: | afterthought | something remembered later |

Stanza 2 (lines 15 – 21) | ||

Line 15: | deranged | very upset, confused, disturbed |

Line 16: | composed | calm |

Line 18: | douches | washes away |

ponds | large pools | |

Line 20: | wrecks | crashed cars |

cling | stick to | |

Line 21: | husks | outside covering |

locusts | large insects like grasshoppers | |

Stanza 3 (lines 22 – 30) | ||

Line 22: | tourniquets | bandages wrapped very tightly to cut off blood supply and so stop bleeding |

Line 23: | splints | something stiff that is tied against a broken bone to stop it moving |

Line 24: | convalescents | people recovering from illness |

intimate | close | |

gauche | awkward | |

Line 25: | sickly | weak |

Line 26: | stubborn | determined |

saw | wise saying | |

Line 27: | grim | gloomy |

banal | ordinary, of little importance, stereotyped | |

resolution | conclusion, decision | |

Stanza 4 (lines 31 – 39) | ||

Line 32: | innocent | not guilty |

Line 34: | suicide | killing oneself |

stillbirth | baby born dead | |

logic | reason | |

Line 36: | occult | magic, the supernatural |

Line 37: | cancels | stops |

physics | science | |

sneer | mocking look | |

Line 38: | spatters | splashes |

denouement | ending of a story that explains everything | |

Line 39: | expedient | useful |

stones | the road | |

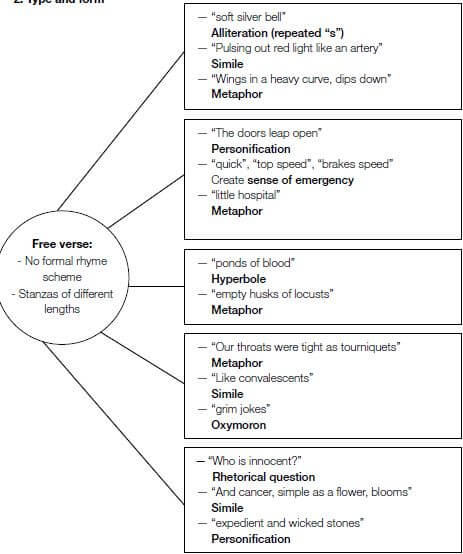

2. Type and form

This is a descriptive poem that deals with thoughts and feelings, so it could be classed as a lyric poem.

The poem is written in free verse, a form of poetry that has no set rhyming pattern. The structure is informal: lines and stanzas may be of different lengths and usually there is no regular use of rhyme, or even no rhyme at all.

3. Analysis

Stanza 1 (lines 1 – 7) Its quick soft silver bell beating, beating, |

These lines describe the arrival of the ambulance at the scene of the car crash (auto wreck). In the 1940s, when this poem was written, ambulances had loud bells, not sirens as they have today. The first few words create a pleasant feeling with the description of the ambulance siren as a “soft silver bell”. Notice how the alliteration of the ‘s’ gives a gentle sound. The repetition of “beating, beating” to describe the strokes of the bell is a harsh contrast.

Then the poet refers to the “dark” of the night and the red “flare” (line 1) as the red light on top of the ambulance approaches. The use of the word “dark” instead of “night” helps to make the scene feel more grim and full of danger.

Note: flare- a light that a ship sends out, like a firework, to show that it is in danger and needs help

The poet then shocks us out of any comfortable feelings we have by using the simile “Pulsing out red light like an artery” in line 3 to describe the light. The flashing light is compared to blood shooting out (“pulsing”) from a blood vessel. This comparison makes us feel that the accident may involve serious injuries, even death. The ambulance speeds along, passing the lights of the signs and clocks on buildings in an ordinary street. The poet compares the ambulance that races to the accident to a large bird coming down to land in the metaphor “Wings... dips down” (line 6). The vehicle brakes and slows to a stop among the crowd of bystanders who always gather at the scene of an accident.

Stanza 2 (lines 8 – 14) The doors leap open, emptying light; |

These lines describe how the accident victims are loaded into the ambulance and driven away. The poet shows the speed and urgency of the paramedics with the personification of the doors that “leap” or jump open, the way, probably, that the paramedics jump quickly out of the ambulance.

Many words the poet uses in stanza 1 – “quick”, “top speed”, “brakes speed”, “leap” – help to give a sense of emergency and haste to the scene. The scene is lit up by the light from inside the ambulance and we see that the victims are extremely badly injured as they are described as being “mangled” (line 9). The word “stowed” (line 10) means “packed away” and could suggest that these people are hurriedly packed into the ambulance as if they are just things or bodies, not living people.

Note: Mangled - twisted and broken

The metaphor “little hospital” (line 10) tells us that the ambulance is equipped to care for the injured. The poet now uses the word “tolls” (line 11) to describe the ambulance bell. This reminds us of a funeral, when the church bell is “tolled” and we suspect that some of the victims may be dying or even dead. This idea is supported when the poet refers to the victims, describes the injured people in the ambulance as “terrible cargo” (line 12).

The ambulance drives off before the doors are closed. This also gives a sense of urgency to the scene as it needs to hurry to save lives. The extended tolling bells also remind us of a funeral; and the “closing” doors suggest that lives may be also be lost (“closed” in line 14). The ambulance now almost becomes a hearse, a vehicle that transports the dead.

Note: The poet vividly describes the movement of the ambulance by using verbs such as 'floating', 'dips' and 'rocking'.

Stanza 3 (lines 15 – 21) We are deranged, walking among the cops |

The crowd is still wandering around at the scene. “Deranged” literally means ‘mentally disturbed’, which shows how much the accident has upset the onlookers. Note that the poet uses the informal word “cops” instead of ‘police’. In contrast to the onlookers, who are very upset, the policemen are calm as they carry out their duties. Could this be because the police are trained to be calm in an emergency and are used to accident scenes? One policeman washes the blood away with water (“douches”), another makes notes and a third one hangs warning lights (“lanterns”) on the remains of the crashed cars.

The hyperbole, “ponds of blood” (line 18), indicates that much blood has been spilled and tells us how badly the victims have been hurt – but notice how easily the signs of pain and suffering are removed with buckets of water. The broken wrecks of the cars are wrapped around the street poles.

The metaphor comparing the wrecked cars to “empty husks of locusts” (line 21) shows how badly the cars are damaged. The images of the husk and locust suggest the torn and broken metal of the cars. Locusts are also very destructive insects. They can eat and destroy crops very quickly; in the same way that an accident can happen quickly and cars can become wrecks.

Note: Husk - The dried-out covering of a plant like a mealie

Stanza 4 (lines 22 – 30) Our throats were tight as tourniquets, |

Note: The stanza shows how shocked the onlookers are.

This stanza focuses on the feelings and reactions of the onlookers. The poet uses medical metaphors to describe the way they feel. Their throats feel as if they are tightly tied up by tourniquets. The shock and horror of the accident makes them unable to move freely, as if their bones have been broken and tied to splints to keep them from moving. These medical metaphors suggest that the onlookers, too, have been hurt (but in their minds, not their bodies). The metaphor “convalescents” (line 24) shows them slowly beginning to recover from the shock, but their smiles are “sickly” and false as they try to hide their horror. They try to make contact (“be intimate”) with one another in an awkward (“gauche”) way.

Some “warn/ With the stubborn saw of common sense” (line 26) – perhaps they are talking about how one should drive more carefully; others make “grim jokes” (line 27). Still others make a “banal resolution”, saying stereotypical things and perhaps using clichés such as, ‘You never know when your turn [to die] is coming’, or decide that they themselves will drive more carefully in future.

There are a number of oxymorons in stanza 3. The onlookers make “grim jokes” (line 27) and they cannot stop thinking about and looking at the accident. It fills their minds with “richest horror” (line 30). We can understand how the accident fills them with horror: the victims could have been themselves or their loved ones, and the accident fills them with the fear of death or dreadful injury.

Note: Oxymoron - Deliberately puts 2 words with opposite meaning together. 'Grim' means horrible or frightening, which is not something we associate with jokes. 'Jokes' have the connotation of laughter and fun.

Stanza 5 (lines 31 – 39) Already old, the question Who shall die? |

In the last stanza, the poet thinks about the mystery of death and its causes. None of us knows how or when we will die, or who will die next: this is the “old ... question” that is in the minds of the onlookers. But this reminds them of another silent question: “Who is innocent?” (line 32). This rhetorical question asks who is responsible for the accident and why those particular people should have been the victims. The poet – and the onlookers – cannot answer the question. Death in an accident like this one does not seem to have a reasonable explanation and is confusing to ordinary people.

Note: Rhetorical question - a question that doesn't really need an answer.

The poet thinks there are reasons for other forms of death that we can understand: people kill one another in war; they kill themselves because of depression or despair; babies are born dead for medical reasons. Diseases like cancer are shown by the simile comparing the way cancer grows inside you to the way a flower blooms (line 35).

The poet feels the only explanation is an “occult” one: only fate – or perhaps God - can explain death in an accident like this. We like to think we can explain everything through science and reason (“physics”), but such accidents make our science useless and mock it (“cancels our physics with a sneer” in line 37). We like to think that life should be like a story in which everything is explained at the end (the “denouement”), but an accident like this is different, and has no easy explanation.

In the final metaphor the poet shows us that the idea of a “denouement” is destroyed, “spattered” like the blood of the victims all over the road. The description of the road (“stones”) is, as we all know, useful (“expedient”), but, being the scene of the accident, it is also personified as “wicked” (line 39) perhaps because without roads and cars there would be no car accidents.

4. Tone and mood

In stanzas 1, the tone is urgent and matter-of-fact as the cleaning up of the accident is described.

In stanza 2, 3 and 4, the tone is confused and horrified as the spectators realise how terrible the accident was.

In stanza 5, the tone is confused and uncertain at the uncertainties of life and death.

The mood of a poem is how it makes the reader feel. How does this poem make you feel? For example, happy, sad, angry, or indifferent.

Summary

Auto wreck by Karl Shapiro

- Theme

Death and the uncertainty of life. - Type and form

- Tone and mood

Tone: Urgent, matter-of-fact, confused, horrified, fearful, uncertain

Mood: How does this poem make you feel? Happy, sad, angry or indifferent? Always give reasons for your answer.

Activity 4

Refer to the poem on page 31 and answer the questions below.

- Complete the following sentences by using the words provided in the list Write only the words next to the question number (1.1–1.3)

This poem describes how the (1.1) … rushes to the scene of the (1.2) … The (1.3) … are picked up and taken to hospital. (3)police van; accident; dead; ambulance; break-down; injured - Refer to stanza

2.1 At what time of the day does this incident happen? (1)

2.2 In lines 4-6 (“The ambulance at ... and illuminated clocks”) the ambulance is compared to a bird. Quote TWO separate words that support this (1) (2) - Choose the correct answer to complete the following Write only the answer (A-D).

The word “mangled” in line 9 tells us that ...- The vehicles are badly damaged.

- Some of the bystanders are very upset.

- The policemen are emotionless.

- The accident victims are seriously injured. (1)

- Refer to lines 15 and 16 (“We are deranged … and composed”).

Quote TWO separate words that show the difference in the reactions of the speaker and the policemen. (2) - Refer to line 25 (“We speak through sickly smiles ...”).

Explain why the onlookers have “sickly smiles”. (2) - Refer to stanza

Using your own words, name TWO things that the onlookers are concerned about. (2) - Complete the following sentences by using the words provided in the list below.

In the last stanza, the speaker argues that there is always a (7.1) ... for Suicide, while stillbirth is (7.2) ... However, a car crash (7.3)... the minds of ordinary people. (3)solution; confuses; reason; unnatural; clarifies; logical - Explain why the poet mentions war, suicide, stillbirth and cancer in a poem about a road (2)

- The poem was first published in Do you think it is still relevant today?

Discuss your view. (2) - Has this poem changed your understanding of the causes of road deaths? Discuss your (2) [22]

Answers to activity 4

|

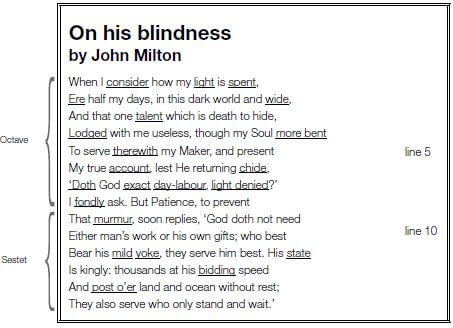

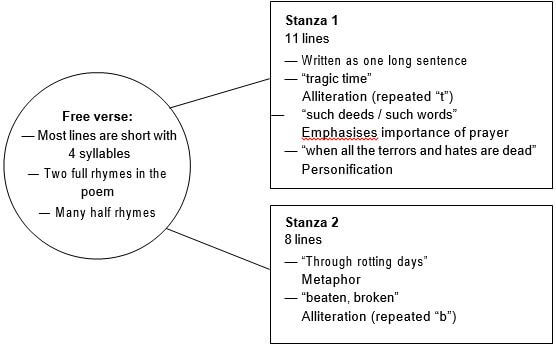

ON HIS BLINDNESS BY JOHN MILTON

On his blindness was written by John Milton (1608-1674). He was a deeply religious English poet. He studied at Cambridge University. As a young man he travelled around Europe and learnt many European languages.

In his later life, there was a civil war in England between King Charles I and Oliver Cromwell and his supporters, who wanted England to become a republic. Milton supported Cromwell and became very politically active. He had to go into hiding when the new king, King Charles II, came into power.

At the age of 44, Milton went blind. Most of his best-known poems were written after this. He composed poems in his head and recited them to his daughters so they could write them down.

Fun fact:

- This poem is based on the parable of the talents in the Bible - Matthew 25, verses 14-30

1. Themes

The main themes in this poem are serving God, blindness (disability) and using one’s talents.

The poet struggles with the fact that he is no longer able to see. He is depressed that he may not be able to serve God by using his talent as a writer. The answer comes to him that God has many followers to do his work and that accepting his blindness and being patient (“stand and wait”) is also serving God

Words to know:

Definitions of words from the poem: | ||

Line 1: | consider | think about |

light | ability to see | |

spent | finished/used up | |

Line 2: | ere | before (old English) |

wide | wild (old English) | |

Line 3: | talent | ability / skill |

Line 4: | lodged | kept in a safe place/ placed |

more bent | more determined; wanting more to do something | |

Line 5: | therewith | with that |

Line 6: | account | report/ record/ explanation |

chide | scold/ show anger/ blame | |

Line 7: | doth | does |

exact | expect/ demand | |

day-labour | work | |

light denied | sight taken away | |

Line 8: | fondly | foolishly |

Line 9: | murmur | quiet complaint |

Line 11: | mild | gentle |

yoke | the rope and wood collar which goes around the neck of an ox to pull a cart | |

state | position/ situation | |

Line 12: | bidding | request/ command |

Line 13: | post o’er | travel over (old English) |

Fun fact:

- The title of this poem was not written by Milton. It was given to the poem much later by Bishop Newton, who was referring to Milton's blindness. That is why it is called, "On his blindness", rather than " On my blindness."

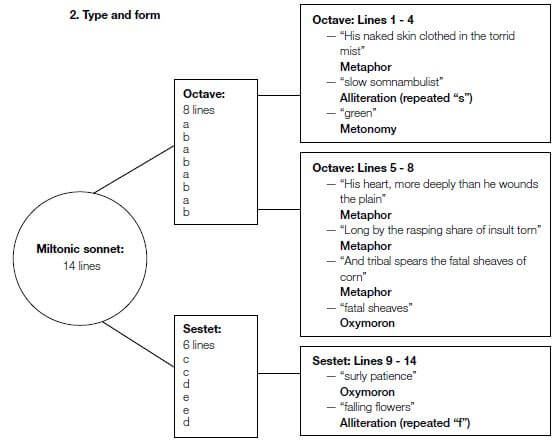

2. Type and form

The poem is an Italian or Miltonic sonnet. This is because its 14 lines are made up of:

- An octave of eight lines made up of two This is where the problem is presented; and

- A sestet of six This is where the problem is resolved. The rhyming scheme in this sonnet is abba abba cdecde.

3.Analysis

The octave (lines 1 – 8) When I consider how my light is spent, |

In the octave, the problem is presented. The speaker feels depressed when he thinks (“consider” in line 1) about his problem – the problem is that he is going blind “ere half my days” – before he is even half way through his life. He has one great gift from God, a “talent”, which has been “lodged” (given to him) to use but it is “useless” (line 4) because he cannot see to write any more.

Fun fact:

- A 'talent' was a coin in the time of the Bible. Jesus used the idea of a 'talent' as something valuable, a skill given by God. To use one's talent or skill was a way of serving God. Hiding one's 'talent' would be an insult to God.

The poet uses a metaphor to refer to his eyesight. He calls it his “light” (line 7). This is an effective comparison because our eyes are important. They are one of the ways we get to understand our world. Light is important

- light allows us to see clearly. Light also represents God and the sun and has connotations of brightness and happiness. This contrasts with the life without light – the “dark world” in line 2.

The poet (or speaker) describes his problem in the octave in one long sentence that ends in the middle of line 8. In this sentence, he lists all the things he is worried about and what may happen as a result of his blindness. He is frustrated because the talent God has given him (“lodged with me”) is “useless” (line 4). He is also frustrated because his soul is absolutely “bent” (determined) on serving his “Maker” (God) (lines 4-5) and he cannot do this if he cannot see.

He is fearful and worried because he knows that God has given him this talent so it would be “death to hide” it (line 3). Milton wants to serve his Maker and use his writing talent so that at the end of his life he can present a good “account” (record of his work) “lest” (in case) God would “chide” (become cross with) him for not using the talent to serve Him (line 6).

The poet is also confused. He says that if God did become angry with him he would ask God how God could demand “day-labour” (work) but at the same time make him blind (“light denied”) and therefore unable to work. Although the poet is frustrated, fearful and a little angry, it is important to note that he remains humble when he speaks to God: he calls God his “Maker”, he is “bent” (wanting / determined) on serving God and he realises that he asks the question foolishly (“fondly” in line 8) because God has a plan we may not know.

Note:

- the poet contrasts light and dark in the poem.

The sestet (lines 9 – 15) But Patience, to prevent |

The sestet is where the problem set out in the octave is resolved. The speaker begins to answer the question in line 8 starting with the word “But”:

But Patience, to prevent

That murmur, soon replies… (lines 8 and 9)

“Patience” (which is a good human quality of being able to wait) seems to appear to him personified almost like an angel from God (in a human form). Notice how Patience is named with a capital ‘P’ – like a proper noun. When Patience appears to him, it is as if the poet’s own mind speaks to him and reassures him.

Patience speaks to stop the poet’s “murmur” (complaints) and explains that God does not need man’s work: people serve God best when they “bear his mild yoke” (obey his gentle commands/ carry a small burden). Patience goes on to explain to the poet that God is so powerful (“His state is kingly” – lines 11 and 12) and that there are “thousands” of others who can serve him in many other places and in many different ways.