HISTORY PAPER 2 GRADE 12 ADDENDUM - 2018 JUNE EXAM PAST PAPERS AND MEMOS

Share via Whatsapp Join our WhatsApp Group Join our Telegram GroupHISTORY PAPER 2

GRADE 12

NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE

MEMORANDUM

JUNE 2018

SECTION A: SOURCE-BASED QUESTIONS

KEY QUESTION: WHAT WAS THE ROLE OF THE SOWETO UPRISING IN THE EVENTUAL DOWNFALL OF THE APARTHEID GOVERNMENT?

SOURCE 1A

This source is an extract from an interview that Tsietsi Mashinini conducted with the ‘The

Daily Sun’ (newspaper) on the 15th of November 1976.

| Question: Could you describe the conditions in the schools and the education system for Blacks in South Africa? Answer: Besides having to buy everything you need at school; you pay high school fees. There are a number of bursaries that are granted on merit, but usually they are granted to students from rich families. The classes have almost eighty pupils in them. There are two or three on a desk even at high school. At primary school level, you sit down on benches in rows with no desks at all. Our schools don’t have heaters. The school simply has a classroom, a blackboard, and the Department of Bantu Education provides the chalk and writing material for the blackboard. Everything else in the classroom is provided by the pupils. In South Africa, the teaching is very impersonal and indifferent. It’s only in rare cases where you find the teacher with an interest in his students or pupils. Most of the time the teacher just comes in, gives you work, and goes out. |

SOURCE 1B

This source is an extract from an interview that Tsietsi Mashinini conducted with the ‘The Daily Sun’ (newspaper) on the 15th of November 1976.

| Question: And now the proposal was to make all teaching in Afrikaans, or just some of it? Answer: Every student is doing seven subjects, at least until high-school level: the two official languages, English and Afrikaans, your mother tongue, and four other subjects. This Afrikaans policy compelled you to do two of the subjects in Afrikaans and two in English. With the type of education, we have and where you do not have much material to research on, students find difficulty in understanding the concepts involved in Physics, Biology, and Geography. And now, if you do all these things in a language you are not conversant in, and the teacher has never been taught to teach in Afrikaans – Afrikaans has got very small circles in society because everywhere the medium of English is used, except in official pamphlets where Afrikaans and English is used – and all the time for almost eleven years you have been taught through the medium of English, it is difficult to switch over. |

SOURCE 1C

This source explains the role that SASO played before the outbreak of the Soweto Uprising.

| Notwithstanding its weakness, SASO was a remarkable, innovative, revolutionary nationalist organisation. Thrust by historical circumstances to play the leading political role in pre-1976 South Africa, SASO rekindled [made it come alive again] black intellectual and political opposition to white domination; its activities helped sow the potential for resistance into fabric of daily life. The accomplishment of SASO and BC movement was to bring about a ‘mental revolution among black youth’, to hand over a new generation of young people that were ‘proud, self-reliant, determined’; and to generate ‘an urban African population psychologically prepared for confrontation with white South Africa’. |

SOURCE 1D

This source explains the local and international response in the aftermath of the Soweto Uprising in 1976.

| The Soweto revolt in 1976 had led to an exodus of some 14 000 black youths from South Africa, providing the ANC in exile with an army of eager new recruits. The capital of Mozambique, Maputo had become a key ANC operational centre. ANC groups had also been set up in Botswana, Swaziland and Lesotho to help establish an internal network and to supervise the flow of recruits. As news of the shooting spread, students went on the rampage, attacking government buildings, beer halls, bottle stores, vehicles and buses. During the first week of the Soweto revolt, at least 150 people were killed, most of them black schoolchildren. Even though the government retreated on the Afrikaans issue, the violence continued. Time and again students returned to the streets, showing remarkable resilience in the face of police firepower and displaying a level of defiance and hatred of the apartheid system rarely seen before. As soon as one set of student leaders was detained or disappeared in exile, others stepped forward, ready to take their place. The spectacle of armed police shooting schoolchildren in the streets brought worldwide condemnation and calls for economic boycotts and sanctions, endangering South Africa’s export markets. Foreign investors no longer looked on South Africa as such a stable and profitable haven. Foreign capital, which had been a vital factor in helping South Africa to achieve high rates of economic growth, began to flow out. Multinational companies with subsidiaries in South Africa faced intense criticism from anti-apartheid groups, some demanding their withdrawal. Several prominent American and British banks terminated their South African business. A United Nations arm embargo had become mandatory in 1977, cutting South Africa off from its last arms supplier, France. |

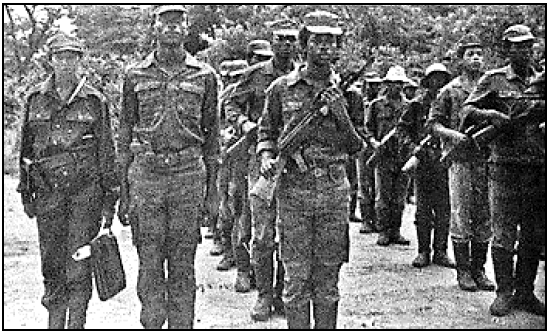

SOURCE 1E

This source by Zolile Nqose depicts MK soldiers in training in Malange Camp in Angola.

QUESTION 2: WHAT HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES WERE EXPOSED BY THE TRC?

SOURCE 2A

This source by Rich Mkhondo, a journalist during and after the apartheid era, explains why he felt that the TRC was an important process for South Africa.

| Well, there are quite a number of issues that we have to remember. The first one is the intention of the Truth Commission. It was to establish the truth of what happened in the past, as much as possible. It’s not possible to establish as fuller the truth as we can, because, for example, there are many people who didn’t testify; there are many people who were forced to testify; and there are many people who lied. For me, it's very important, because it confirms some of the things that I witnessed as a journalist. It confirms some of the suspicions that we had about some of the disappearances of some of our friends, some of our colleagues and so on. I have a lot of friends who died, who were killed mysteriously. And now I know. And I have family members who didn’t know where their loved ones were. And through the commission people came and said, I know, I'm the one who buried so and so; I can go and point the space where the – the spot where the person is buried. And then the Truth Commission people went there and exhumed the bodies, and the people are given decent funerals ... ... I think the most important thing to remember here is now we know. Now we know. It's quite important to emphasise that. Now we know what happened. You know, during the bad days of apartheid, there were many people, particularly white South Africans, who lived in Cloud Kukula. They just didn't want to know what was going on in the townships ... |

SOURCE 2B

This is an extract of the experience of Richard Lyster, a Commissioner in the TRC, who witnessed the exhumation of the body of Portia Ndwandwe. Portia, an MK soldier in Natal, was ABDUCTED and KILLED by police outside Pietermaritzburg after she refused to become a police informer.

| To me this was the most poignant (emotional) and saddest of all exhumations, (digging up of a body) for a number of reasons. She was a woman, then the extreme remoteness of the terrain, and the conditions of her detention and death. She was held in a small concrete chamber on the edge of the small forest in which she was buried. According to information from those that killed her, she was held naked and interrogated in this chamber, for some time prior to her death. When we exhumed her body, she was on her back in a fetal position, because the grave had not been dug long enough, and she had a single bullet wound to the top of her head, indicating that she had been kneeling or squatting when she was killed. Her pelvis was clothed in a plastic bag, fashioned into a pair of panties indicating an attempt to protect her modesty. She must have heard them digging her grave? |

SOURCE 2C

This source is an extract from Zahrah Narkedien testimony before the TRC. She was arrested and placed in solitary confinement, another form of TORTURE used by the security forces. She was held alone in a cell the size of a small bathroom for seven months.

| I don’t even want to describe psychologically what I had to do to survive down there. I will write it one day but I could never tell you. It did teach me something and that is that no human being can live alone for more than I think a month ... I became so psychologically damaged that I used to feel that all these cells are like coffins and there were all dead people in there, because they were not there, no one was there. It was as if I was alive and all these people were dead ... I’m out of prison now for more than seven or ten years but I haven’t recovered and I will never recover ... I have tried to and the more I struggle to be normal, the more disturbed I become. I had to accept that I was damaged, a part of my soul was eaten away as if by maggots ... and I will never get it back again. [From Truth, Justice, Memory: South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Process, Institute for Justice and Reconciliation] |

SOURCE 2D

This is an extract from Clive Derby-Lewis’ amnesty application hearing before the TRC where George Bizos asked him whether he had apologised for the murder of Hani.

| BIZOS: Mr Derby-Lewis, you made an attempt to apologise, firstly in your statement where you actually apologise to the people of your side and the trouble you gave for your arrest. Correct? DERBY-LEWIS: That’s correct. BIZOS: No apology for the killing or Mr Hani? DERBY-LEWIS: No, Mr Chairman. BIZOS: Have you apologised about wasting a valuable life that may have made a valuable contribution to the people of SA, Mr Derby-Lewis? DERBY-LEWIS: With respect Mr Chair, may I ask is this a condition and is this something that the commission should be subjected to evidence? My impression was that an apology was not necessary and part of the function of this committee. JUDGE MALL: Mr Bizos, the Act does not require an applicant to apologise for what he did, it requires a full disclosure of what he did. BIZOS: I’m not asking as a question of law. I’m asking whether this person who is before you have ever expressed regret for killing a person who could have made a valuable contribution to the political life of this country or not. DERBY-LEWIS: Mr Chairman, no, how can I ever apologise for an act of war, war is war. I haven’t heard the ANC apologising, the perpetrators of these deeds apologising for killing people in pubs, blowing them up in Wimpy Bars, I have heard no apology, Mr Chairman. Those people were just as important as Mr Hani was. |

SOURCE 2E

This source explains how Anne-Marie McGregor testified before the TRC to find out if it was her son that she had buried and how he had died. Her son, Wallace, was on a ‘callup’ in the South African Army when he was killed during the war in Namibia in 1986. He was nineteen when he died. The army presented her with her son’s body in a bag and asked her not to open it and to respect the military code of secrecy. During the TRC process she found out how her son had died through a young man, ‘Michael’ who had served with Wallace.

What I cannot forget, however, is that as Michael finally came to the point where he described Wallace's actual death, Mrs McGregor said, ‘So Wallace is rêrig dood.’ (‘So Wallace is really dead.’). I realised then that for more than ten years, because she had not been able to see her son's body ... Mrs McGregor had been unable to come to terms with the fact that her son was dead. She had sustained the vain hope that it had been the wrong body, that one day she would find him again.  |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Visual sources and other historical evidence were taken from the following:

www.dailysun.co.za

Dr Badat M S, The South African Students Organisation (SASO) and the Biko Legacy www.sahistory.org.za

http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/umkhonto-wesizwe-mk-exile

http://www.pbs.org/newshouribb/africa/july-dec98/southafrica_10-29.htmt

http://www.religion.emory.edu/affiliate/COVR/Vicencio.htunt

Truth, Justice, Memory: South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Process, Institute for Justice and Reconciliation

www.doj.gov.za/trc/amntrans/index.htm

Wendy O, From Biko to Basson

Meredith M, The State of Africa – A History of fifty years of independence