HISTORY PAPER 1 GRADE 12 ADDENDUM - NSC EXAMS PAST PAPERS AND MEMOS NOVEMBER 2020

Share via Whatsapp Join our WhatsApp Group Join our Telegram GroupHISTORY PAPER 1

GRADE 12

NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE

ADDENDUM

NOVEMBER 2020

QUESTION 1: HOW DID THE SOVIET UNION AND THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA CONTRIBUTE TO COLD WAR TENSIONS IN CUBA IN THE 1960s?

SOURCE 1A

The source below focuses on why Cuba and the Soviet Union became allies in the early 1960s.

When Fidel Castro came to power in Cuba, his relations with the United States of America got worse. Castro was not a communist but became close to Nikita Khrushchev (leader of the Soviet Union) because of his support and friendship. Later diplomatic and commercial relations between Cuba and the Soviet Union were established. Castro nationalised all banks and US-owned companies and refused to pay compensation.

The USA responded by cutting off all diplomatic and commercial ties with Cuba in 1961. Castro responded by announcing that Cuba was now implementing communism as a political ideology. The US government reacted by imposing a trade embargo on all Cuban goods. This meant that Cuba did not have a market for its sugar and tobacco produce. This forced Cuba to sell its produce to the Soviet Union and in return Cuba purchased oil and weapons from the Soviet Union …

Khrushchev and the Soviets couldn't have asked for a better-located ally (friend) against the United States of America (USA). The Americans had allies all over the Eastern Hemisphere surrounding the USSR. The USA had a huge number of military forces in Europe near Soviet borders … It was well known that the United States had nuclear missiles in Turkey which were pointed at the Soviet Union.

By the time John F Kennedy became president at the beginning of 1961, the Americans were already working on ways to get rid of Castro … This plan ended in disaster with the failed battle at the Bay of Pigs in April 1961. Castro and his army quickly defeated the US sponsored rebels and the failure was a huge embarrassment for Kennedy's administration … This helped to solidify (strengthen) Castro's alliance with the Soviet Union.

[From The Cuban Missile Crisis – To the Brink of War by Paul J Byrne]

SOURCE 1B

This source is part of a statement that Nikita Khrushchev made on 11 September 1962. It outlines how the Soviet Union assisted Cuba economically and militarily.

We do not hide from the world public that we really are supplying Cuba with resources such as industrial equipment and goods which are helping to strengthen her economy and to raise the well-being of the Cuban people.

… a certain amount of armaments is also being shipped from the Soviet Union to Cuba at the request of the Cuban government because of aggressive threats by imperialists. Castro also requested the Soviet government to send military specialists and technicians to Cuba who would train the Cubans in handling up-to-date weapons which require high skills and in-depth knowledge. It is but natural that Cuba does not yet have such specialists. That is why we considered this request. It must, however, be said that the number of Soviet military specialists sent to Cuba can in no way be compared to the number of workers in agriculture and industry sent there. The armaments and military equipment sent to Cuba are designed exclusively for defensive purposes. The President of the United States and the American military know what means of defence are. How can these means threaten the United States?

We have said, and we do repeat, that if war is unleashed (started), if the aggressor makes an attack on one state or another and this state asks for assistance, the Soviet Union has the possibility from its own territory to render assistance to any peace-loving state and not only to Cuba …

We do not say this to frighten someone. Intimidation (bullying) is alien (unknown) to the foreign policy of the Soviet State. Threats and blackmail are an integral part of the imperialist states. The Soviet Union stands for peace and wants no war.

[From http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/precrisis.htm. Accessed on 21 August 2019.]

SOURCE 1C

The source below focuses on how President Kennedy reacted to the deployment of Soviet missiles to Cuba.

All Americans, as well as all of our friends in this Hemisphere, have been concerned over the Soviet Union's role to bolster (strengthen) the military power of the Castro regime in Cuba. Information has reached this government in the last four days from a variety of sources which establishes without doubt that the Soviets have provided the Cuban government with a number of anti-aircraft defence missiles with a range of twenty-five miles ... Along with these missiles, the Soviets are apparently providing the extensive radar (sensor) and other electronic equipment which is required for their operation.

We can also confirm the presence of several Soviet-made motor torpedo boats carrying ship-to-ship guided missiles having a range of fifteen miles. The number of Soviet military technicians now known to be in Cuba or en route is approximately 3 500 and is consistent with assistance in setting up and learning to use this equipment. As I stated last week, we shall continue to make information available as fast as it is obtained and properly verified (checked).

The Cuban question must be considered as a part of the worldwide challenge posed by the communist threat to democracy, peace, stability and prosperity. It must be dealt with as a part of that larger issue as well as in the context of the special relationships which have long characterised the inter-American system.

It continues to be the policy of the United States that the Castro regime will not be allowed to export its aggressive purposes by force or the threat of force. It will be prevented by whatever means may be necessary from taking action against any part of the Western Hemisphere.

[From http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/jfkstate.htm. Accessed on 19 August 2019.]

SOURCE 1D

The headline below is taken from an American newspaper, The Arizona Republic, published on 23 October 1962. The headline reads 'U.S. BLOCKADES CUBA, TELLS RUSS "LAY OFF" '.

QUESTION 2: WHAT IMPACT DID THE BATTLE OF CUITO CUANAVALE HAVE ON SOUTH AFRICA AND CUBA?

SOURCE 2A

The source below discusses the defeat of the South African Defence Force (SADF) by the Cuban military forces at the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale.

In 1987 to 1988, the myth (fiction) of the invincibility (cannot be defeated) of the South African military machine was laid to rest, with important consequences for social change. In July 1987, the South African Defence Force (SADF) launched a major attack into south-eastern Angola. This was an attempt to prevent the Angolan government forces from capturing the town of Mavinga from UNITA and to extend the area under UNITA control. The South African and UNITA forces met unexpectedly strong resistance from Angolan (MPLA) and Cuban forces around the town of Cuito Cuanavale.

Despite the arrival of fresh SADF reinforcements in December 1987 and the use of their most destructive and sophisticated weapons, such as aircraft, artillery, tanks and armoured cars, they still suffered heavy casualties and failed to capture Cuito Cuanavale. Meanwhile other Angolan (MPLA) and Cuban military forces moved towards the Namibian border and cut off South Africa's line of retreat (withdrawal).

Decisive in the SADF's defeat was the loss of air superiority. The South African Air Force found itself unable to match the modern Soviet equipment brought into battle by the defenders. South African aircraft were unable to penetrate the radar/missile defences at Cuito Cuanavale and when the Cuban forces launched an air strike on the Calueque Dam in June 1988, the SADF air defence proved inadequate.

[From Foundations of the New South Africa by J Pampallis]

SOURCE 2B

The source below explains the consequences of the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale.

Nonetheless, the commitment of Cuban troops had radically altered (changed) the balance of power in southern Africa. The prospect of more white conscripts being killed by a well-armed Cuban adversary (enemy), the cost of the war and the impact it had on South Africa's economy prompted (pressured) South Africa to leave Cuito Cuanavale.

In April 1988, PW Botha's cabinet agreed to begin direct negotiations with Angola and Cuba under Chester Crocker's (US Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs) mediation. As the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) concluded, 'military considerations weighed most heavily in Pretoria's decision to negotiate', elaborating that 'for the first time in modern history, its leadership was unnerved (frightened) by the prospect of a well-armed adversary (enemy) able to inflict (cause) serious casualties on South African forces in conventional warfare … causing President PW Botha and his senior advisers to accept reluctantly a truce (peace) and the idea of negotiating Namibian independence in exchange for Cuban troop withdrawal'.

A flurry (series) of negotiations now gradually brought Crocker's linkage plan closer to reality. Although it would take twelve rounds of talks, on 22 December 1988 two treaties were signed at the United Nations Organisation, one between Angola and Cuba arranging the withdrawal of Cuban troops, the other among Angola, Cuba and South Africa agreeing to Namibian independence. Crocker's long fight was over, his goal of brokering (negotiating) a regional peace deal was realised at last.

[From Journal of Southern African Studies, volume 35, number 1: Chester Crocker and the South African Border War, 1981–1989. A Reappraisal of Linkage by Z Kagan-Guthrie]

SOURCE 2C

The source below is an extract from a letter written by Oscar Oramas Oliva (Cuban representative at the Security Council of the United Nations Organisation) to the President of the Security Council on 22 December 1988. It includes the terms of the tripartite peace agreement that Cuba, South Africa and Angola signed.

Cuba and Angola agree that the question of the independence of Namibia and the safeguarding of the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of Angola are closely linked to peace and security in the south-western region of Africa; that a tripartite agreement between Cuba, Angola and South Africa, containing the essential elements for the achievement of peace in the south-western region of Africa, is to be signed.

We now therefore hold it to be established that the conditions have been created which permit the commencement of the return to its homeland of the Cuban military contingent (delegation) now present in Angolan territory, which has successfully fulfilled its internationalist mission. We accordingly agree as follows:

ARTICLE 1

The … phased and total withdrawal to Cuba of the 50 000 man contingent of Cuban troops.

ARTICLE 3

Both parties request the Security Council to carry out verification (confirmation) of the redeployment and the phased and total withdrawal of the Cuban troops from the territory of Angola …

ARTICLE 4

This Agreement shall come into force upon the signature of the tripartite agreement between Cuba, Angola and South Africa.

The withdrawal of the Cuban forces should be according to the following timeframes: By 1 November 1989: 25 000; by 1 April 1990: 33 000; by 1 October 1990: 38 000 and by 1 July 1991: 50 000.

[From https://peacemaker.un.org/angola-protocol-brazzaville88. Accessed on 11 September 2019.]

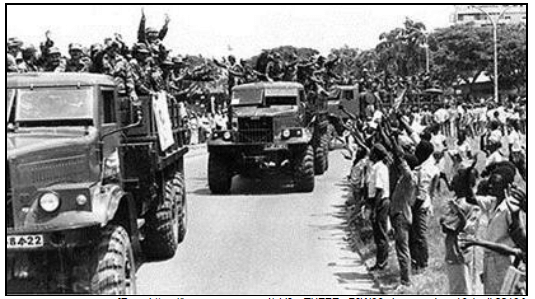

SOURCE 2D

The photograph below shows Cuban soldiers leaving Angola after the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale. The photograph was taken on 10 January 1989. The photographer is unknown.

QUESTION 3: WHAT PROGRAMMES DID THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY IMPLEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA IN THE 1960s?

SOURCE 3A

The source below focuses on the reasons for the establishment of community-based programmes by the Black Panther Party in the United States of America in the 1960s.

Famous for taking up guns in defence against police brutality, the members of the Black Panther Party had many other little known sides to their work. They organised community programmes [for African Americans] such as free breakfast for children, health clinics and shoes for children …

The programmes were of key importance in the Panthers' strategy. Firstly they fed the hungry, gave out food, clothing and medical care to poverty-stricken African Americans. Secondly, it showed what could be achieved if you were organised …

'A lot of people misunderstand the politics of these programmes; some people refer to them as reform programmes. They're not reform programmes, they're actually revolutionary community programmes. A revolutionary programme is started by revolutionaries, by those who want to change the existing system for a better system. A reform programme is set up by the existing exploitative system as an appeasing (peace-making) hand-out, to fool the people and to keep them quiet …'

The first programme the Panthers organised was the Free Breakfast for Children. Lesley Johnson explains how this led her to get involved in the Panthers. 'Well, one of the things that I could immediately respect and admire the party for was its Breakfast for School Children Programme. You know my parents were both workers ... And there were times when I was growing up, the week's oatmeal or whatever would run out and I went to school hungry. So I really appreciated what the party was doing.'

[From http://www.socialistalternative.orge-black-panther-party-for-self-defense/.

Accessed on 13 March 2019.]

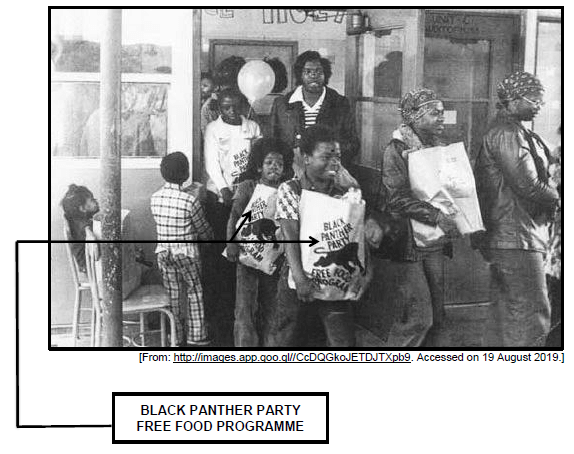

SOURCE 3B

The photograph below shows African American women and children carrying free food bags that were distributed at the Black Panther Party offices in Oakland, California in 1969.

SOURCE 3C

The extract below is taken from a speech that was delivered by Ericka Huggins (activist of the Black Panther Party) at the Alternative Schools Conference on 23 and 24 May 1976. It focuses on how the Oakland Community School contributed to the upliftment of African American children in the United States of America.

This city needs to organise to get things done in education, housing and the courts and to also uplift the lives of the African Americans. I wanted to say that before I went on to talk about education …

I talked yesterday about the Oakland Community School, about alternative education and community schools. I'd like to begin today to give you a history of the Oakland Community School, why we started it, whom it serves and in what direction we feel we're heading.

First, we don't call ourselves an 'alternative school.' We know that we are, but the word 'alternative' has taken on such a negative meaning with black and poor people that in analysing who we were, whom we were serving and what we were trying to do, we decided to call ourselves a 'model school'.

We call Oakland Community School a 'model school' and it is. We serve 125 children. We're located in East Oakland. We serve children who have been labelled 'educationally disadvantaged', 'economically deprived' and 'uneducable'. We're working with children, who would be in public schools; who have not been to private schools or other alternatives; whose parents have no political affiliation (connection) and just want their children to have the best. I know we all want the best for our children. Children deserve the best because they are the future.

So, in 1971, as a result of harassment (persecution) that some children were getting in Oakland, (by some children I mean sons and daughters of members of the Black Panther Party) a group of parents and instructors got together and decided to form what was then called the Inter-communal Youth Institute in Oakland.

[From https://i.pinimg.com/originals/ee/c4/45/eec445e67979686e86227c6c0f86d32b.jpg.

Accessed on 13 March 2019.]

SOURCE 3D

The source below focuses on the strategies that the Federal Bureau of Intelligence (FBI) used to disrupt the community programmes of the Black Panther Party.

Free food seemed relatively innocuous (harmless), but not to FBI head, J Edgar Hoover, who loathed (hated) the Black Panther Party (BPP) and declared war against them in 1969. He (Edgar Hoover) called the (Free Food) programme 'potentially the greatest threat to efforts by state authorities to destroy and render the BPP ineffective and what it stands for', and gave carte blanche (complete freedom) to law enforcement agencies to crush it.

The results were swift (sudden) and devastating (shocking). FBI agents went door-to-door in cities like Richmond in Virginia, telling parents that members of the BPP would teach their children about black nationalism. In San Francisco, writes historian Franziska Meister, parents were told the food was infected with contagious (spreadable) disease; free food sites in Oakland and Baltimore were raided by officers who harassed BPP members in front of terrified children, and participating children were photographed by the Chicago police.

'The night before the first breakfast programme in Chicago was supposed to open', a female Panther told historian Nik Heynan, 'the Chicago police broke into the church and mashed up all the food and urinated on it'.

Ultimately, these and other efforts to destroy the Black Panthers broke up the programme. In the end, though, the public visibility of the Panthers' breakfast programmes put pressure on political leaders to feed children before school …

… In 1975, the School Breakfast Programme was permanently authorised. Today, it helps feed over 14,57 million children before school and without the radical actions of the Black Panthers, it may never have happened.

[From http://www.history.com/news/free-school-breakfast-black-panther-party.

Accessed on 16 May 2019.]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Visual sources and other historical evidence were taken from the following:

Byrne, PJ. 2006. The Cuban Missile Crisis – To the Brink of War (Compass Point Books, Minneapolis, Minnesota)

http://images.app.goo.gl//CcDQGkoJETDJTXpb9

http://www.history.com/news/free-school-breakfast-black-panther-party

http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/jfkstate.htm.

http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/precrisis.htm.

http://www.socialistalternative.orge-black-panther-party-for-self-defense

https://govbooktalk.gpo.gov/2012/10/18/hawks-vs-doves-the-joint-chiefs-and-the-cuban-missile-crisis/

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/ee/c4/45/eec445e67979686e86227c6c0f86d32b.jpg

https://images.app.goo.gl/eV3xyTXEZEqr79W96

https://peacemaker.un.org/angola-protocol-brazzaville88

Kagan-Guthrie, Z. 1995. Journal of Southern African Studies, Volume 35, Number 1: Chester Crocker and the South African Border War, 1981–1989. A Reappraisal of Linkage

Pampallis, J. 1991. Foundations of the New South Africa (Maskew Miller, Cape Town)