HISTORY PAPER 2 GRADE 12 ADDENDUM - NSC PAST PAPERS AND MEMOS NOVEMBER 2021

Share via Whatsapp Join our WhatsApp Group Join our Telegram GroupQUESTION 1: HOW DID THE UNITED DEMOCRATIC FRONT (UDF) RESPOND TO THE APARTHEID REFORMS INTRODUCED BY PW BOTHA IN 1983?

SOURCE 1A

The source below explains the reasons why PW Botha, President of the Republic of South Africa, introduced reforms in 1983.

… in early 1983, Botha attempted to ease the mounting pressures on the country by introducing some piecemeal reforms to the apartheid policy without relinquishing (giving up) white minority control. He scrapped what he called 'outdated' and 'unnecessary' apartheid statutes (laws), such as the outlawing of mixed marriages and sex across colour line, to present a new image of reformism (change) to the world. It almost succeeded. The Western powers, ever eager to read the South African situation optimistically (positively), were deceived for a time into believing that Botha was really dismantling apartheid. But, on a closer examination, when Botha unveiled constitutional changes he intended making, it became clear what he had in mind was not reform but rather a reformulation (restructuring) of apartheid. He set out his plan to establish a tricameral parliament in which the mixed-race 'Coloured' and Indian minorities would have separate chambers to legislate their 'own affairs', while the existing much larger, whites-only House of Assembly would deal with both 'whites issues' and the nation's 'general affairs'. The huge black majority, meanwhile, would get nothing beyond the right to vote in their remote tribal Bantustans, and the municipal councils would run their separate black townships in so-called 'white' South Africa. But even these urban councils were not autonomous (free). The legislation enabled the white minister to remove members, appoint others, or dismiss the whole council and appoint a new one. It meant that the black councils had to implement government policy rather than be responsive to their electorates. [From Tutu – The Authorised Portrait by A Sparks and MA Tutu] |

SOURCE 1B

The source below is an extract from a speech delivered by Rev. Dr Allan Boesak at the launch of the United Democratic Front (UDF) at the Rocklands Civic Centre, in Mitchells Plain on 20 August 1983. It focuses on the formation and intensions of the UDF.

We have arrived at a historic moment. We have brought together, under the aegis (protection) of the United Democratic Front (UDF), the broadest and most significant coalition of groups and organisations struggling against apartheid, racism and injustice since the early nineteen fifties. We have been able to create a unity amongst freedom-loving people this country has not seen for many a year. I am particularly happy to note that this meeting is not merely a gathering of loose individuals. No, we represent organisations deeply rooted in the struggle for justice, deeply in the heart of our people. We are here to say that the government's constitutional proposals are inadequate, and that they do not express the will of the vast majority of South Africa's people. … The most important reason for us coming together here today is the continuation of the government's apartheid policies as seen in the constitutional proposals. … All the basic laws, which are the very pillars of apartheid, indeed, those laws without which the system cannot survive – group areas, racial classification, separate and unequal education, to name but a few – remain untouched and unchanged. The homelands policy forms the basis of the wilful exclusion of 80% of our nation from the new political deal. Clearly the oppression will continue, the apartheid line is not all abolished. [From RUNNING WITH HORSES – REFLECTIONS OF AN ACCIDENTAL POLITICIAN by A Boesak] |

SOURCE 1C

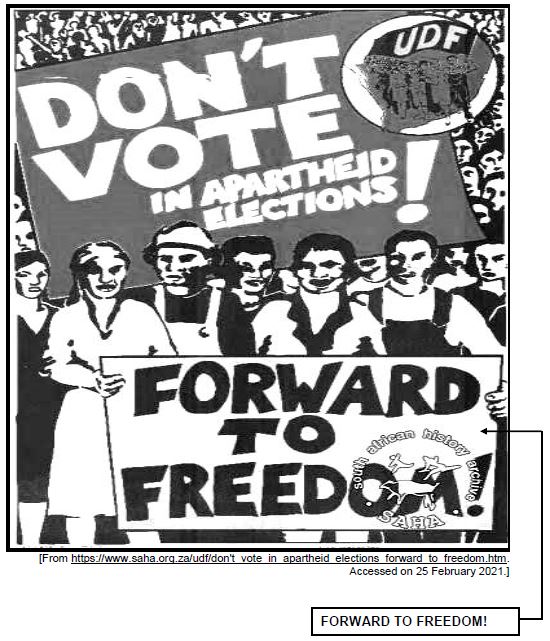

The poster below, published and distributed by the UDF in 1983, is directed at Botha's

call for elections for a tricameral parliament. It urges all white, Coloured and Indian

South Africans not to participate in the apartheid elections.

[From https://www.saha.org.za/udf/don't_vote_in_apartheid_elections_forward_to_freedom.htm.

SOURCE 1D

The source below, taken from a newspaper article titled 'Indian Turnout about 20% in South African Elections', was written by Allister Sparks for the Washington Post on 29 August 1984. It explains why there was a low turn-out from both Indians and Coloureds in the tricameral elections in 1984.

About 20 per cent of the registered voters in South Africa's Indian community appeared to have voted today in elections for a new parliament that were marked by sporadic violence between boycotters and police in several cities. The results available tonight indicated that members of the 870 000-strong Indian community stayed away from the polls in even larger numbers than the mixed-race Coloured electorate did in last week's voting for representatives in the racially compartmentalised (classified) tricameral parliament. There was a 30 per cent turnout at the elections for the larger Coloured community. The government declared that figure adequate for pressing ahead with plans to implement its new constitution, but other observers labelled it a rebuff (refusal). Since many people who were eligible to vote did not register, particularly among the Coloureds, leaders of the boycott movement were claiming tonight that the effective vote in the two elections was about 18 per cent out of a joint population of 3,5 million. The movement said this represented a 'massive rejection' of the white minority government's new constitution, which offers the Coloured and Indian minority groups a form of parliamentary representation for the first time, but continues to exclude the black African majority. White voters endorsed the constitution by a two-thirds majority at a referendum last November, and the United States State Department joined in praising the government of President PW Botha for taking 'a step in the right direction.' [From Washington Post, 29 August 1984] |

QUESTION 2: HOW DID THE TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION (TRC) DEAL WITH THE MURDER OF THE POLITICAL ACTIVIST, GRIFFITHS MXENGE?

SOURCE 2A

The extract below focuses on the reasons for the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 1995.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was a court-like body assembled in South Africa after the end of apartheid. Anybody who felt they had been a victim of violence could come forward and be heard at the TRC. Perpetrators of violence could also give testimony and request amnesty from prosecution. The hearings made international news and many sessions were broadcast on national television. The TRC was a crucial component of the transition to full and free democracy in South Africa and, despite some flaws, is generally regarded as very successful. The mandate of the commission was to bear witness to, record and, in some cases, grant amnesty to the perpetrators of crimes relating to human rights violations, reparation and rehabilitation. The work of the TRC was accomplished through three committees: the Human Rights Violations (HRV) Committee investigated human rights abuses that took place between 1960 and 1994, the Reparation and Rehabilitation (R&R) Committee was charged with restoring victims' dignity and formulating proposals to assist with rehabilitation and the Amnesty Committee (AC) considered applications for amnesty that were requested in accordance with the provisions of the Act. In theory the commission was empowered to grant amnesty to those charged with atrocities during apartheid as long as two conditions were met: the crimes were politically motivated and the whole truth was told by the person seeking amnesty. No one was exempt from being charged. [From: Du Toit, F, et al. 2006 Truth and Reconciliation in South Africa: 10 Years On (David Philip)] |

SOURCE 2B

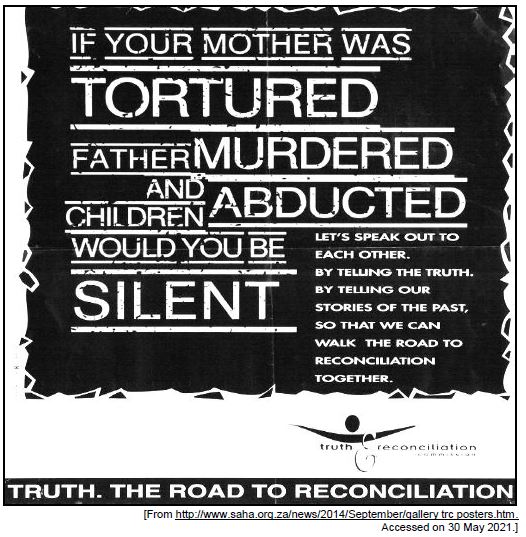

The poster below was produced by the TRC. It invites both perpetrators and victims to appear before the TRC and testify about human rights abuses that were committed between 1960 and 1994.

[From http://www.saha.org.za/news/2014/September/gallery trc posters.htm.

SOURCE 2C

The extract below is part of the testimony that Dirk Coetzee, death squad commander at Vlakplaas, gave at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's (TRC's) public hearing into the murder of political activist Griffiths Mxenge. The hearing was held in Durban on 5 November 1996.

MR JANSEN: Did you give the members of the team any instructions as far as the way in which the murder had to be committed? MR DIRK COETZEE: Yes, I did, Mr. Chairman. I said they should specifically not use guns, and must make it look like a robbery, and it was decided on knives, that Mr Mxenge will be killed with knives. MR JANSEN: Did you give them any further instructions as to how they should go about achieving that goal? MR DIRK COETZEE: They took his car away, they parked it in the parking lot between CR Swart Square and the magistrate's court … and I left. I then went to Warrant Officer Paul van Dyk and Constable Braam du Preez, whom I gave instructions to take Mr Mxenge's car and leave for Golela border post … I then went to … Brigadier Van der Hoven … and reported to him … that Mr Mxenge was killed. I said the only people that were reported to me that did the stabbing of Mr Mxenge were Joe Mamasela, Almond Nofomela and David Tshikalanga. MR JANSEN: And on the probabilities, who would those orders have come from headquarters? MR DIRK COETZEE: He told me it was orders from Brigadier Skoon … MR JANSEN: And what was the purpose of burning the car near the Swaziland border? MR DIRK COETZEE: To give the impression that the murder was committed by ANC cadres as a result of a quarrel … and then they fled back to Swaziland and burnt the car before crossing the border. [From www.justice.gov.za/trc/report/. Accessed on 30 May 2021.] |

SOURCE 2D

The source below has been taken from a newspaper article titled 'Coetzee Gets Amnesty for Mxenge Murder' that appeared in the Mail & Guardian on 4 August 1997. It focuses on the outcome of the amnesty application by Dirk Coetzee and his two accomplices.

COETZEE GETS AMNESTY FOR MXENGE MURDER 4 Aug. 1997 [From Mail & Guardian, 4 August 1997] |

QUESTION 3: WHAT IMPACT HAS THE GLOBAL COVID-19 PANDEMIC HAD ON SOUTH AFRICA?

SOURCE 3A

The source below has been taken from an article written by S Kitenge, titled 'Globalisation and the Covid-19 pandemic: How is Africa's economy impacted?' It focuses on how globalisation contributed to the spread of Covid-19.

Since the rise of globalisation, the world has become more closely connected and people can easily interact with one other without facing any serious barriers. This has been both beneficial and detrimental (negative) to the social, political and economic spheres as far as the welfare of people is concerned. The free movement of people, goods and services brought about by globalisation have stimulated socio-economic development, but it has also become a channel for the spread of diseases. As a result of the technological developments associated with globalisation an outbreak, such as Covid-19, has turned into a major pandemic that affects people around the world regardless of their geographical location. According to K Lee, globalisation is defined as the 'changing nature of human interaction across a wide range of spheres including economic, political, social, technological and environmental … The process of change can be described as globalising in the sense that the boundaries of various kinds are becoming eroded'. Thus, it is fair to assert that globalisation, which made free movement of people from different cities, countries and continents possible, is the main enabler (source) of the spread of Covid-19 around the world. This is simply because technological advancement, which is one of the main forces for globalisation, has made it easier for people to travel by land, sea and air from one part of the world to another without facing any obstacles. If travellers have contracted a disease, such as Covid-19, in city or country (A), they can easily transmit it to the previously non-infected city or country (B) … [From https://www.policycenter.ma/sites/default/files/PB_20-37_Seleman.pdf. |

SOURCE 3B

The source below is an extract from a speech delivered by President Cyril Ramaphosa on 15 March 2020. The speech deals with the measures that have to be taken to combat the spread of Covid-19 in South Africa.

Fellow South Africans, I am addressing you this evening on a matter of great national importance. The world is facing a medical emergency far graver (serious) than what we have experienced in over a century. The World Health Organisation has declared the coronavirus outbreak as a global pandemic. There are now more than 162 000 people who have tested positive for the coronavirus across the globe. Given the scale and the speed at which the virus is spreading, it is now clear that no country is immune (safe) from the disease or will be spared its severe impact. From the start of the outbreak in China earlier this year, the South African government has put in place measures to screen visitors entering the country, to contain its spread and to treat those infected. As of now, South Africa has 61 confirmed cases of people infected with the virus, and this number is expected to rise in the coming days and weeks. Following an extensive analysis of the progression of the disease worldwide and in South Africa, Cabinet has decided on the following measures: Firstly, to limit contact between persons who may be infected and South African citizens, we are imposing a travel ban on foreign nationals from high-risk countries, such as Italy, Iran, South Korea, Spain, Germany, the United States, the United Kingdom and China as from 18 March 2020. South African citizens are advised to refrain (hold back) from all forms of travel to or through the European Union, United States, United Kingdom and other identified high-risk countries such as China, Iran and South Korea. It is true that we are facing a grave (serious) emergency. But if we act together, if we act now, and if we act decisively, we will overcome it. I thank you. [From https://www.gov.za/speeches/statement-president-cyril-ramaphosa-measures-combat-Covid-19-epidemic-15-mar-2020-0000. Accessed on 6 June 2021.] |

SOURCE 3C

The source below is part of an article written by Vuyokazi Futshane (project officer of Oxfam South Africa) for the online magazine, The Conversation. It focuses on the economic impact that lockdown regulations have had in South Africa.

Poverty and inequality have been heightened (increased) by the Covid-19 pandemic. When South Africa went into a hard lockdown on 26 March 2020, many informal workers and precarious (irregular) workers found themselves without any means of generating income. Many of these workers are black women, whose families are reliant (dependent) on them for their survival. The National Income Dynamics Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey estimated that nearly three million people had lost their jobs because of the pandemic and the official unemployment rate now stands at a shockingly high rate of 30,1%. South Africans are now more afraid of unemployment than the coronavirus: unemployment is more than a state of joblessness, it means worrying about being able to afford everyday basic necessities, how to send children to school, how to stay healthy and nourished (fed) and it means worrying about being able to access health care should anything happen … Townships and informal settlements whose demographic profile is predominately black people and people of colour who are employed in low-paying jobs that increase their risk of exposure to Covid-19, have become Covid-19 hotspots. This is because of dynamics, such as spatial planning, that hold the legacies of apartheid, such as the Group Areas Act in 1950 where black and non-white South Africans were forced to relocate to the areas outside of major cities and economic hubs (centres). These areas are still largely underdeveloped, overly populated, have poor sanitation facilities, lack of running water in many low-income communities and a poorly structured public healthcare system. The pandemic is exposing how persistent the various factors of inequality are heightening the devastating effects of Covid-19. [From https://theconversation.com/covid-19-has-hurt-some-more-than-others-south-africa-needs-policies-that-reflect-this-151923. Accessed on 26 May 2021.] |

SOURCE 3D

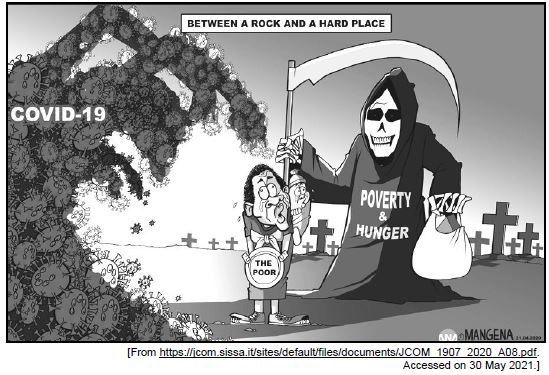

The cartoon below, by H Mangena, appeared in an online publication of the African News Agency on 21 April 2020. The cartoon highlights the challenges faced by the poor as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

[From https://jcom.sissa.it/sites/default/files/documents/JCOM_1907_2020_A08.pdf.

Accessed on 30 May 2021.]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Visual sources and other historical evidence were taken from the following:

Boesak, A. 2009. RUNNING WITH HORSES – REFLECTIONS OF AN ACCIDENTAL POLITICIAN (Joho Publishers, Cape Town)

Du Toit, F, et al. 2006 Truth and Reconciliation in South Africa: 10 Years On (David Philip)

http://www.saha.org.za/news/2014/September/gallery trc posters.htm

https://jcom.sissa.it/sites/default/files/documents/JCOM_1907_2020_A08.pdf

https://www.policycenter.ma/sites/default/files/PB_20-37_Seleman.pdf

https://www.saha.org.za/udf/don't_vote_in_apartheid_elections_forward_to_freedom. htm

Mail & Guardian, 4 August 1997

Sparks, A and Tutu, MA. 2011. Tutu – The Authorised Portrait (Macmillan, Johannesburg)

Washington Post, 29 August 1984

www.justice.gov.za/trc/report/