HISTORY PAPER 1 GRADE 12 ADDENDUM - NSC EXAMS PAST PAPERS AND MEMOS MAY/JUNE 2021

Share via Whatsapp Join our WhatsApp Group Join our Telegram GroupHISTORY PAPER 1

GRADE 12

NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE EXAMINATIONS

MAY/JUNE 2021

QUESTION 1: HOW DID THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA RESPOND TO THE DEPLOYMENT OF SOVIET MISSILES TO CUBA IN 1962?

SOURCE 1A

The source below explains how the United States of America (USA) reacted to the Soviet Union's deployment of missiles to Cuba in 1962.

Throughout 1962, the movement of Soviet personnel and equipment to Cuba aroused (awakened) suspicions in the American intelligence community. In response, US ships and planes began to take photographs of every Cuban-bound Soviet vessel and U-2 spy planes began regular reconnaissance (exploration) flights over the island.

The first evidence of the arrival of surface-to-air missiles, missiles equipped with torpedo boats for coastal defence and large numbers of Soviet military personnel in Cuba, came in photographs taken late in August. But these photographs provided no evidence of offensive ballistic missiles. In September, Kennedy delivered two explicit (clear) warnings to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev regarding the build-up of what was being called 'defensive' Soviet arms in Cuba.

On 13 September, Kennedy wrote, 'If at any time the communist build-up in Cuba were to endanger or interfere with our security in any way, or if Cuba should ever become an offensive military base of significant capacity for the Soviet Union, then this country will do whatever must be done to protect its own security and that of its allies.'

Despite Kennedy's warnings, the Soviets continued to construct bases, and the United States continued to monitor their activities and take photographs. On 14 October 1962 an American U-2 spy plane took several photographs while flying over Cuba. These photographs revealed that the Soviet Union was busy building missile sites in Cuba. This changed the nature of the game and set in motion a series of extraordinary events.

SOURCE 1B

This source is an extract from an interview that was conducted with Robert McNamara, while he was US Foreign Secretary (Minister of Defence) from 1961 to 1968. The transcipt of the interview was declassified on 29 November 1998. It outlines the decision taken by the USA to impose a naval quarantine on Cuba.

INTERVIEWER: Could you just explain to me briefly how the decision to quarantine evolved? I'm quite interested to hear about the change of mood within the ExComm or change of opinion.

ROBERT McNAMARA: The ExComm came to the unanimous (common) conclusion that it was necessary, in the interest of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation's (NATO's) security, Western Europe security and US security, to pressure the Soviets in ways that would lead to removal of the missiles. Secondly, we wished to do that with as little military risk as possible; as little military risk in the pressure itself and as little risk of military response after that initial step was taken. It was believed that what was called a 'quarantine' (which in a sense was a naval blockade) was called a quarantine because a quarantine had less of a military connotation than 'blockade' ... it was believed that the quarantine would convey to Khrushchev the determination of the President to see that those missiles were removed, without stimulating a military response, and that's why the quarantine was approved.

INTERVIEWER: Was there much discussion about what to do if the Soviet Union decided to ignore the quarantine?

ROBERT McNAMARA: Yes, there was, and that led to some very acrimonious (unpleasant) confrontations. It was decided that we would make every possible effort to avoid sinking a Soviet ship. There was a famous incident involving the chief of naval operations and myself. A Soviet ship was approaching this imaginary quarantine line and the question was, how would we react when it reached the quarantine line? The chief of naval operations in effect said that if it didn't stop, we'd fire on it. And I responded that there would be no firing on that Soviet ship without my personal permission, and I would not give it without having discussed the action with the President, because he and I were determined to avoid military action if we possibly could. As I suggested, we did not think of quarantine as military action, but as a means of communicating intent (purpose) and determination, the President wanted the missiles removed with as little military risk as possible.

SOURCE 1C

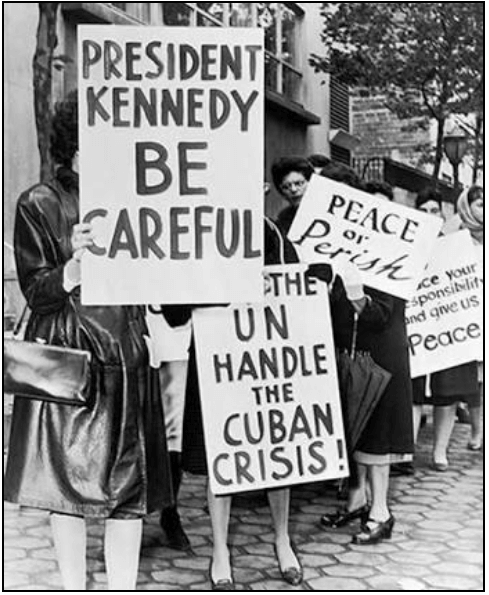

The photograph below shows a group of American women who belonged to the 'Women Strike for Peace' Movement, protesting outside the United Nations (UN) building on 23 October 1962. The photograph was taken by Phil Stanziola and appeared in the World Telegram and Sun newspapers.

SOURCE 1D

The source below is part of a letter that President N Khrushchev wrote to President JF Kennedy on 24 October 1962. It explains the Soviet Union's response to the US naval quarantine of Soviet ships that intended entering Cuba.

Dear Mr President

... Imagine, Mr President, what if we were to present to you such an ultimatum as you have presented to us by your actions. … You, Mr President, are not declaring quarantine, but rather issuing an ultimatum, and you are threatening that if we do not obey your orders, you will then use force.

… No, Mr President, I cannot agree to this … We firmly adhere to the principles of international law and strictly observe the standards regulating navigation on the open sea, in international waters. We observe these standards and enjoy the rights recognised by all nations.

… Unfortunately, people of all nations, and not least the American people themselves, could suffer heavily from madness such as this. Since the appearance of modern types of weapons, the USA has completely lost its former inaccessibility (not reachable).

… The Soviet government considers the violation of the freedom of navigation in international waters and air space to constitute an act of aggression, propelling (pushing) humankind onto the brink (edge) of a global nuclear-missile war. Therefore, the Soviet government cannot instruct captains of Soviet ships bound for Cuba to observe orders of American naval forces blockading this island. Our instructions to Soviet sailors are to observe strictly the generally accepted standards of navigation in international waters and not retreat one step from them. And, if the American side violates these rights, it must be aware of the responsibility it will bear for this act. To be sure, we will not remain mere observers of pirate actions by American ships in the open sea. We will then be forced on our part to take those measures we deem (consider) necessary and sufficient to defend our rights. To this end we have all that is necessary …

QUESTION 2: HOW DID CUBA SUPPORT THE POPULAR MOVEMENT FOR THE LIBERATION OF ANGOLA (MPLA) DURING THE ANGOLAN CIVIL WAR OF 1975?

SOURCE 2A

This source is part of a letter that Commander Manuel Piñeiro Losada (Vice-Minister of the Interior in Cuba) wrote to the Cuban Minister of the Revolutionary Armed Forces in July 1975. It focuses on how Cuba intended to assist the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA).

For some time now we have discussed the possibility of entering Angola with the objective of getting to know the revolutionary movements in that country. These movements have been a mystery (secret) even for those socialist countries that gave them considerable aid. I don't consider it necessary to explain the strategic importance of these countries.

Our comrades in the MPLA solicited (requested) us this May for the following:

- That we train 10 men in Cuba in guerrilla warfare, taking into account the positive experiences they have had with people trained in Cuba (they are the heads of various guerrilla forces).

- That we send a crew to fly a DC-3 (aeroplane) from Zambia or the Congo to Angola, transporting equipment for the guerrillas. They explained that because of great distances between the Northern Front and the borders with Zambia and the Congo, it is extremely difficult to maintain the supplies by land and that it is from that front where they have contacts and are planning activities in the capital Luanda, which have military and political importance.

- They want to send a high-level delegation to Cuba to discuss relations with our Party.

We suggested it was a good idea to send some of our comrades to the interior of Angola to learn about the terrain (landscape) and to shoot a film, which they agreed to, and they proposed postponing their requests until the return of our delegation. The delegation would be protected by 150 troops directed by one of the commanders trained in Cuba ...

Commander Manuel Piñeiro Losada

Vice-Minister of the Interior

SOURCE 2B

The source below is taken from Conflicting Missions – Havana, Washington, Pretoria by P Gleijeses. It explains the military support that Cuba gave to the MPLA in 1975.

After holding a series of meetings with Agostinho Neto, the leader of the MPLA, the chief of the Cuban contingent (group), Brigadier-General Raul Diaz Argüelles, and his team drew up plans for the implementation of a Cuban training programme which could satisfy all of Neto's requirements. The training programme, as proposed by Argüelles, included 480 Cuban specialists and the set-up of four camps within Angola located in Cabinda, Salazar (N'Dalatando), Benguela and Henrique de Carvalho (Saurimo). Over the next six months, the Cubans would train 4 800 MPLA recruits into 16 infantry battalions and supply 25 mortar batteries as well as various anti-aircraft units.

On 21 August 1975, an advance party of this Cuban Military Mission in Angola (Misión Militar Cubana en Angola – MMCA), under the command of Argüelles, arrived in Luanda. Argüelles would report directly to the First Deputy Minister of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces (FAR), General Abelardo Colomé Ibarra, who was in overall command of the operation.

According to the original plan, 191 Cubans would be sent to the camp in the Cabinda enclave (hideout), under the command of General Ramón Espinosa Martín. The remaining 270 would be evenly split among the remaining three camps. The reason for the relatively large contingent of Cuban soldiers that were deployed to Cabinda, was its vulnerability (exposure) to an attack by the FNLA and its Zairian allies.

On 30 September 1975, the first 70 Cubans of the Cabinda contingent flew out of Havana via Barbados and Bissau to Brazzaville where they were transferred to a Congolese Antonov aeroplane for the short flight to Pointe-Noire, completing their journey to Cabinda by road. The Cuban army had arrived on Africa's shores and it would not take long before it crossed swords with the SADF and its allies, the FNLA and UNITA.

SOURCE 2C

The source below outlines how Cuba deployed its first batch of soldiers to Angola in 1975. It was written by a Colombian author, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and appeared in The Washington Post on 12 January 1977.

On 7 November 1975, on the eve of Angola's independence from Portugal, Cuba launched a large-scale military intervention, Operation Carlota, to support the MPLA. Their mission was to hold back the offensive so that the Angolan capital would not fall into enemy hands before the Portuguese left, and then to keep up the resistance until reinforcements arrived. Operation Carlota began with the sending of a reinforced battalion of special forces, made up of 650 men. They were flown over a span of 13 days from the military section of the Jose Marti Airport in Havana to the airport in Luanda, still occupied by Portuguese troops.

The first contingent (group) left at 16:00 on 7 November on a special flight of Cubana de Aviacion, on one of the legendary Bristol Britannia 318 airplanes that the English manufacturers had stopped making and the rest of the world had stopped using.

The passengers all wore summer clothes, with no military insignia (badges) and carried briefcases and regular passports with their real names and identification.

The members of the special battalion were well-trained warriors with a high level of political and ideological formation. But in their briefcases they carried machine pistols, and in the cargo hold of the plane, instead of the baggage, there was a substantial (large) load of light artillery, small arms, three 75 mm cannons and three 82 mm mortars.

SOURCE 2D

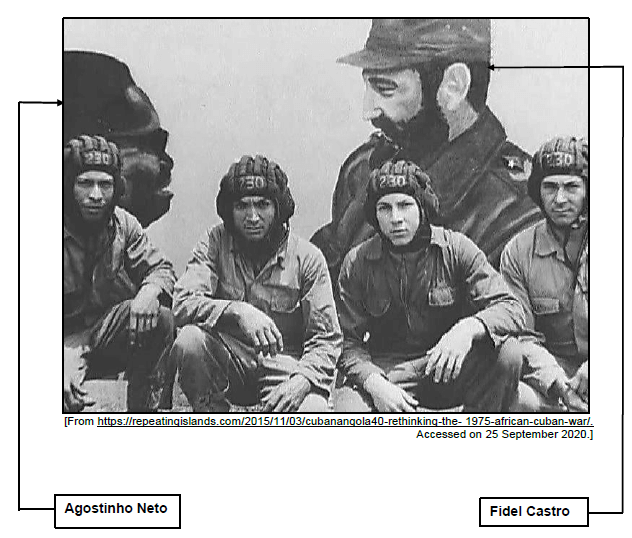

The photograph below was taken on 3 November 2015. It shows troops from Cuba's military air wing that were invited to Angola for the 40th commemoration of Operation Carlota. The photographer is unknown.

QUESTION 3: WHAT ROLE DID ELAINE BROWN PLAY IN THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY DURING THE 1960s AND 1970s?

SOURCE 3A

The source below was written by John Simkin for Spartacus Education in September 1977. It explains how Elaine Brown became a member of the Black Panther Party.

Elaine Brown credited her early political education to Jay Kennedy, a member of the American Communist Party, and the piano lessons she gave in the Watts Housing Project in the summer of 1967. Her experiences in Watts served as a social and racial awakening and later Brown began writing for the radical African-American newspaper, Harambee. Brown's first direct exposure to the Black Panther Party (BPP) came through local appeals for the Huey Newton Legal Defence Fund. As a member of the Los Angeles chapter of the Black Panther Party, Brown helped establish the party's first Free Breakfast for Children programme outside of Oakland, California. By 1971, Brown became editor of the party paper, The Black Panther and was soon appointed the first female member of the Panther Central Committee. At Huey Newton's directive, Elaine Brown made her first run for Oakland City Council in 1973, in tandem (together) with Bobby Seale's mayoral bid. Although neither Brown nor Seale were elected, both won solid support of a politically reawakened black Oakland population which led to an expansion of the Panther's constituency. In 1974, Huey Newton ousted Panther Party co-founder, Bobby Seale, from the party and two days later Brown was appointed to the position of chairwoman of the Black Panther Party. When Newton fled to Cuba, Brown consolidated (strengthened) her position as leader of the male-dominated party and worked to redefine the Panthers' revolutionary programme to include the aspirations of black women.

SOURCE 3B

The source below focuses on Elaine Brown, chairperson of the Black Panther Party (BPP), addressing members at a meeting in Oakland, California on 6 August 1974.

Elaine Brown assumed her position as the first female leader of the Black Panther Party. Surrounded on stage by the Panthers security personnel, she looked into the audience of party members and with two succinct (concise) sentences took her place in African-American history. 'I have all the guns and the money. I can withstand challenge from without and from within,' Brown told BPP members according to her 1992 memoir, A Taste of Power: A Black Woman's Story. 'I haven't called you together to make threats, Comrades. I've called this meeting simply to let you know the realities of our situation. The fact is Comrade Huey Newton is in exile. The other fact is, I'm taking his place until we make it possible for him to return from Cuba.' For the Panthers, choosing a woman to lead the party was in itself revolutionary.

She warned against a coup (take-over) by stating, 'If you are such an individual, you'd better run and fast. I, as your chairperson, the leader of this party, I would not allow my leadership to be challenged. I will lead our party both above ground and underground. I will lead the party not only in furthering our goals, but also in defending the party by any and all means possible.'

Elaine Brown's powerful speech to members of the Panthers showed her great leadership skills. She was not afraid to take a firm stand and challenge her male counterparts. Brown served as an inspiration for African-American youth and women in particular …

SOURCE 3C

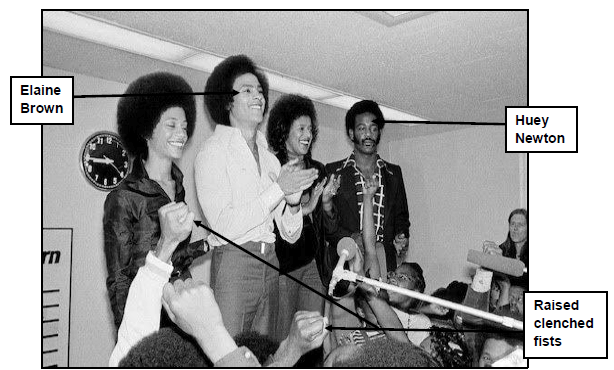

The photograph below shows Elaine Brown, leader of the Black Panther Party, welcoming Huey Newton back to the United States of America after being exiled to Cuba. The photograph was taken by Jim Palmer for the Associated Press (AP) at the San Diego International Airport on 14 July 1977.

SOURCE 3D

The source below is part of an interview that was conducted by Louis Massiah and Terry Rockefeller for the Washington University Libraries, with Elaine Brown, on 14 October 1988. It focuses on the challenges that the Black Panther Party faced.

LOUIS MASSIAH: What did it mean to be a Black Panther? What was a Black Panther?

ELAINE BROWN: Well, as an individual, it meant committing your life. We had to surrender up something of ourselves, our lives.

LOUIS MASSIAH: How did that year, 1969, start?

ELAINE BROWN: Well, it started with the assassinations (killings) of John Huggins and Bunchy Carter in Los Angeles. And, for me, every month I went to a funeral. Ah, I became a professional singer at funerals. E Hoover, the fascist Director of the FBI, had stated at the beginning of that year that it would be the last year the Black Panther Party would exist. And we knew we had to confront that. We had what we called the Executive Mandate Number One, which was that no Panther could ever allow himself or herself to lose a gun.

LOUIS MASSIAH: Go on with the deaths.

ELAINE BROWN: Well, 1969, in the Black Panther Party, it was a very rough year for all of us. But we thought we would be able to handle ourselves. The Executive Mandate Number One, issued by Huey Newton, said the Panthers, first of all, always had to be armed whether on the streets or at home, in order to defend ourselves there and then. As a result of our activities and Hoover's part, we lost a whole lot of people. And I went to a funeral every month in 1969, there was no joke about what was going on. But we believed with our hearts that we should defend ourselves. And there were so many that did do that. And so many died, by the end of the year, in the raid on the Los Angeles office by the Los Angeles Police SWAT Team, a five-and-a-half hour attack on our offices, with tanks and paramilitary rifles, etc. We knew this was serious, and we would all die, but that was what we were about. We had to pay the price, if we wanted to be the vanguard (forerunner) for the emancipation (liberation) of African Americans …

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Visual sources and other historical evidence were taken from the following:

Gleijeses, P. (2003) Conflicting Missions – Havana, Washington, Pretoria (Galago, Cape Town)

http://www.greenleft.otg.au/contest/angola-honours-cuba-crucial-contribution-freedom-struggle

http://www.ibiblio.org/expo/soviet.exhibit/x2jfk.html

http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/01/19/i-have-all-the-guns-and-money-when-a-woman-led-the-black-panther-party/

https://digital.wustl.edu/e/eii/eiiweb/bro5427.0311.022marc_record_interviewer process.html

https://narchives2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB67

https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/coldwar/interviews/episode-10/mcnamara2.html

https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2002/fall/cuban-missiles.html

https://www.bajanthings.com/operation-carlotta--cuba-secret-flights-to-angola-via-barbados

https://www.spartacus-education.com

https://images.app.goo.gl/e5u154rjea2JPqEZ6

https://repeatingislands.com/2015/11/03/cubanangola40-rethinking-the-1975-african-cuban-war