HISTORY PAPER 2 GRADE 12 ADDENDUM - NSC EXAMS PAST PAPERS AND MEMOS MAY/JUNE 2021

Share via Whatsapp Join our WhatsApp Group Join our Telegram GroupHISTORY PAPER

GRADE 12

NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE EXAMINATIONS

MAY/JUNE 2021

ADDENDUM

QUESTION 1: WHAT WERE THE RESPONSES TO THE COMPULSORY INTRODUCTION OF AFRIKAANS AS A MEDIUM OF INSTRUCTION IN BLACK SOUTH AFRICAN SCHOOLS IN 1976?

SOURCE 1A

The source below focuses on the Department of Bantu Education's decision to impose Afrikaans as a compulsory medium of instruction on black South African schools.

The issue that caused the 1976 Soweto Uprising was a decree (law) issued by the Department of Bantu Education. The Deputy Minister of Bantu Education, Andries Treurnicht, sent a directive to school boards, inspectors and principals that Afrikaans should be put on an equal basis with English and had to be used as a medium of instruction in all schools. These instructions drew immediate negative reaction from various teacher organisations and school boards both inside and outside Soweto.

The first body to formally respond to the imposition of the apartheid regime's language policy was the Tswana School Board, which comprised (made up) school boards from Meadowlands, Orlando West, Dobsonville and other areas in Soweto. The minutes of the meeting of the Tswana School Board that was held on 20 January 1976 read:

'The circuit inspector told the Board that the Secretary for Bantu Education has stated that all direct taxes paid by the black population of South Africa are being sent to the various homelands for educational purposes there … In urban areas the education of a black child is being paid for by the white population, that is English and Afrikaans-speaking groups. Therefore, the Secretary for Bantu Education has the responsibility of satisfying the English and Afrikaans-speaking people. Consequently, as the only way of satisfying both groups, the medium of instruction in all schools shall be on a 50-50 basis ... In future, if schools teach through a medium not prescribed by the Department for a particular subject, examination question papers will only be set in that medium with no option for other languages.'

The Tswana School Board made several attempts to get the Department of Bantu Education to end this policy, but it resulted in failure. School boards were told in no uncertain terms that the language policy must be implemented. Most school boards simply gave in to this directive …

SOURCE 1B

The article below was written by Nelvis Qekema and is titled 'The June 16 Uprising Unshackled: A Black Perspective'. It focuses on how the philosophy of Black Consciousness influenced black South African students to challenge the use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction.

… No matter how painful it might be, it is a fact of history that the 16 June 1976 Uprising occurred under the direct influence of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM). On 28 May 1976 the South African Students' Movement (SASM), a student component of the BCM, held its general students' council meeting where the issue of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction was discussed. The minutes of the general students' council meeting captured the spirit of the meeting and stated that the recent boycotts at schools were a demonstration against preparing 'good industrial boys' for the powers that be … 'We resolve to totally reject the use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction …'

Seth Mazibuko gave this testimony at his 1977 trial and stated the following: 'On 13 June 1976, I attended this meeting. Various schools from Soweto were present. The main speaker explained to us what the aims and objectives of the SASM were. He also discussed the use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction and called upon the prefects at our schools to come forward and to explain what the position was [in their schools]. I stood up and told the congregation that Phefeni [Junior Secondary] School refused to use Afrikaans and they had boycotted classes during May 1976.'

On 13 June 1976, at an SASM meeting an Action Committee was formed. It was named the Soweto Students' Representative Council (SSRC) which was led by Tsietsi Mashinini. A decision was taken for a planned march on 16 June against the compulsory use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction in black South African schools.

SOURCE 1C

The source below focuses on how events unfolded in Soweto on 16 June 1976.

On the morning of 16 June 1976 a massive crowd of students gathered on Vilikazi Street opposite Phefeni Junior Secondary School and Orlando West High School in Soweto.

Chanting slogans, such as 'Away with Afrikaans', 'Amandla Ngawethu' (Power to the People) and 'Free Azania', the huge crowd had attracted scores of people, including the apartheid police force …

Five white police officers stood side by side in the middle of the road and faced a sea of black faces. Behind them, more uniformed police, most of them black and from the riot squad, armed with rifles and accompanied by dogs, alighted (got out of) from police trucks. They walked down the road towards the officers and the massive group of students. Several women watched from the roadside. 'Are you going kill our children?' a woman asked an African police officer as he walked past. 'No, there'll be no shooting,' said the officer calmly. 'The children are not fighting anybody, they are only demonstrating …'

Suddenly a white police officer stepped to the side, bent down and picked up what seemed to be a stone. He then hurled the object into the crowd. Instantly the children in front of the column scattered to the sides. They picked up stones and regrouped. They shouted, 'Power, P-o-w-e-r!' as they advanced towards the police. 'Bang,' a shot rang out, then another and yet another in rapid succession.

Students fled in all directions, many took refuge (shelter) on the rugged ridge behind the two schools, into alley ways, side streets and homes. Everybody seemed terribly shaken. The students were bewildered (confused) and grim (shocked). They had not expected this. Dumb-struck, they stood in groups all over the area while the wounded lay groaning on the ground. Helped by motorists and journalists, they collected the dead and the wounded and took them to hospitals.

SOURCE 1D

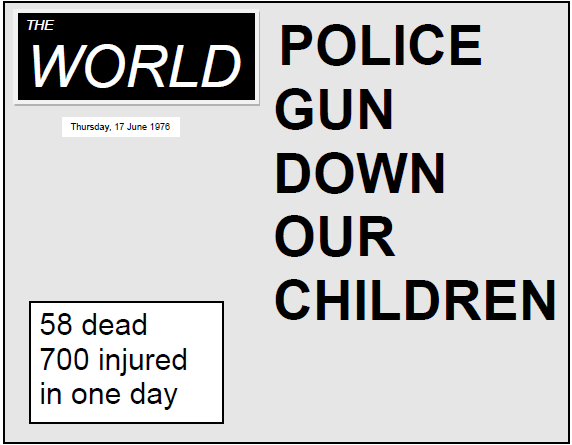

The headlines below appeared on the front page of The World newspaper on 17 June 1976. It was titled 'POLICE GUN DOWN OUR CHILDREN'. The World newspaper was mainly read by black South Africans. It has been re-typed for clarity.

QUESTION 2: HOW DID THE TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION (TRC) DEAL WITH THE MURDER OF POLITICAL ACTIVISTS SUCH AS LENNY NAIDU?

SOURCE 2A

The source below was written by historian, Martin Meredith. It focuses on the reasons for the formation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

The honeymoon (celebratory) period came to an end over differences of how to deal with South Africa's violent past. Nelson Mandela was determined that human rights violations during the apartheid era should be investigated by a truth commission. The purpose, he noted, was not to exact retribution (revenge) but to provide some form of public accountability and to help purge (remove) the injustices of the past so that reconciliation can take place. Unless past crimes were addressed, he said, they would 'live with us like a festering (decaying) sore'. FW de Klerk, deputy president in Mandela's government of national unity, denounced (criticised) the whole idea, arguing that a truth commission would result in a 'witch hunt' focusing upon past government abuses while ignoring the crimes committed by the African National Congress. It was, he said, likely to 'tear the stitches of wounds that are beginning to heal' …

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) that emerged in 1995 was born inevitably of compromise. Its scope was limited to the investigation of gross violations of human rights, such as murder, abduction (kidnapping) and the use of torture in the thirty-four-year period from 1960, starting with the massacre at Sharpeville …

The TRC was given powers of subpoena (demand) and of search and seizure and it was supported by its own investigative unit. It was required to pay as much attention to human rights violations that were committed by the liberation movement as by the apartheid security police. But it was not a judicial body or a court of law. It could not carry out prosecutions or hand out punishment. Its aim was not so much to reach a judgement about culpability (blame) as to establish a process of disclosure. In exchange for telling the truth, perpetrators who came forward were granted amnesty from prosecution on an individual basis, provided the Commission was satisfied that they had made full disclosure of their crimes and their actions had been carried out with a political objective. If they failed to come forward, they would remain at risk of prosecution.

SOURCE 2B

The source below is a transcript (written record) of evidence that Leslie Naidu gave before the TRC regarding the murder of his brother and student activist Lenny Naidu. The TRC hearing was held at the Durban Christian Centre on 30 July 1999.

COMMISSIONER: You have come to tell us also about the death of your brother, Surendra Lenny Naidu, who was also killed by the security forces in 1988 at Piet Retief. Can you please stand to take the oath before you tell us that story ...? LESLIE NAIDU: … I come to the Commission as the spokesperson for my family to give evidence on the events surrounding the death of my brother Lenny. Firstly, I was very pleased to hear of the establishment of the TRC, and it was something that we prayed and hoped for the last 10 years and it has been almost 11 years since I last saw my brother alive. We always believed in truth and justice and it was something that we always thought will always win, whether it's today, tomorrow, or in 10 years' time. And it was this philosophy that really made me think about myself and look into myself after Lenny had died and I asked myself, firstly, do I want justice as we believed in this philosophy of justice and fair play? Do I want justice to be served onto the wrongdoers, especially those that had administered justice the way they did to my brother and the people of this country? Do I want it to be meted out (done) in the very same manner? And there were times I wanted this type of justice, I wanted this jungle justice, blood for blood, and an eye for an eye, but fortunately there were times I wanted to learn the truth. And those times that I wanted to learn the truth actually calmed me in my need for such justice. Truth is what we all want and truth, I think, is what we deserve now. But the most soul-searching part comes after truth, and that is forgiveness. I had to think long and hard about forgiveness. … But what do I forgive, who do I forgive? It seems this road of forgiveness, or this battle that I have with forgiveness seems to be going around in circles all the time. Until this road straightens up perhaps I can forgive. But through this Commission I hope that these perpetrators will give us the truth and only the truth.

SOURCE 2C

The newspaper article below focuses on Eugene De Kock's appearance before the TRC. It was written by Archie Mini for the Independent Online website on 26 July 1999. The perpetrators were not granted amnesty for the murder of the nine political activists.

Eugene de Kock, the apartheid assassin (killer), appeared before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission at the Durban Christian Centre on Monday. De Kock and 14 other former security branch policemen applied for amnesty for their involvement in three incidents of murder, where they killed nine ANC members from KwaZulu-Natal in four days during 1988. In the first incident, Surendra 'Lenny' Naidu (23), Notsikelelo Cotoza (25), Makhosi Nyoka (25) and Lindiwe Mthembu (21), died when their car was ambushed in Houtkop Road outside Piet Retief in Mpumalanga, on the night of 8 June 1988. Six people, Leon William Flores, Jury Bernardus Hayes, Gerrie Johan Barnard, Flip Koenraad Theron, Frederick Johannes Pienaar and Marthinus David Ras, are applying for amnesty with De Kock for the killing of the four MK operatives, who were unarmed when they came under fire. The families of the dead are opposing the application. De Kock told Judge Morane Moerane, representing the family of the deceased, that he organised the ambush after a request was sent to him by 'a Mr Pienaar', former head of the security branch in Piet Retief, to 'help them with an operation concerning trained ANC members infiltrating (entering) the country from Swaziland'. 'They had to give a signal of a flashing left indicator to let us know that the occupants were armed. In both cases the signals were made, according to De Kock. To cover up the shooting of unarmed combatants 'we planted a Makarov pistol on the body of Lenny Naidu and a hand grenade in one of the bags of the women'. 'We are opposing the application for amnesty,' said Leo Naidu, Lenny's father.

SOURCE 2D

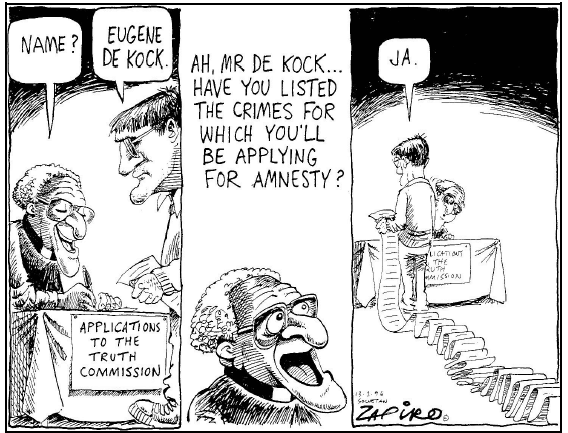

The cartoon by Zapiro below depicts Archbishop Desmond Tutu receiving Eugene de Kock's application for amnesty. It was published in the Sowetan on 13 March 1996.

QUESTION 3: WHAT ARE THE DIFFERENT VIEWS REGARDING THE IMPACT OF GLOBALISATION ON DEVELOPING COUNTRIES?

SOURCE 3A

The article below focuses on how globalisation influences the economies of developing countries. It was written by F Hamdi and the title is 'The Impact of Globalisation on Developing Countries'.

Globalisation helps developing countries to increase their economic growth and solve poverty problems in their respective countries. In the past, developing countries were not able to tap the world economy due to trade barriers. They could not share the same economic growth as developed countries. However, with globalisation, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund encouraged developing countries to go through market reforms and make radical (drastic) changes by taking large loans. Many developing nations began to take steps to open their markets by removing tariffs and freeing up their economies. The developed countries were able to invest in the developing nations and create job opportunities for the poor. For example, rapid growth in India and China led to a reduction in global poverty. It is clear that globalisation has made the relations between developed countries and developing nations stronger …

Globalisation has many economic and trade advantages for developing countries, but underdeveloped countries are faced with many disadvantages. For instance, globalisation increases the inequality between the rich and poor because the benefits of globalisation are not universal, the rich are getting richer and the poor are becoming poorer. Many developing countries benefit from globalisation but, then again, many of these nations do stay behind. In the past two decades, China and India have grown faster than many rich nations. However, countries in Africa have not grown and still have the highest poverty rates in the world ...

SOURCE 3B

The source below is an interview conducted by the Global Business Social Enterprise with N Pavcnik, an associate professor of Economics at Yale University on globalisation. The interview was conducted in New Hampshire, in the United States of America (USA), in 2005.

INTERVIEWER: Is there a way to describe, in a broad sense, what impact globalisation has had on the poorest people living in underdeveloped countries?

N PAVCNIK: If you look back over the past 30 years, developing countries had increased levels of trade protection which have led to higher trade barriers being imposed (forced) on imports and contributed to limited imports. During the 1980s and 1990s, many countries decided to abandon these protectionist (defensive) policies and implemented large-scale trade reforms. For example, India implemented trade reforms in 1991 and its average tax on imports dropped from over 80% to an average of 30%. Colombia went from 50% to around 13%. This has resulted in increased trade flows.

Economic growth is the main channel through which globalisation can affect poverty. What researchers have found is that, in general, when countries open up for trade, they tend to grow faster and living standards tend to increase. The usual argument goes that the benefits of this higher growth will trickle down to the poor. It has been a bit challenging, especially with aggregate (combined) data, to pinpoint (identify) how exactly the poor have benefited. One challenge is that when trade or globalisation happens, many other factors change, such as technology and macro-economic conditions.

But, that said, it is virtually impossible to find cases of poor countries that were able to grow over long periods of time without creating trading opportunities. And we have no evidence to suggest that trade leads to increased poverty and a decline in growth.

INTERVIEWER: Are poverty and inequality seen as a threat to globalisation?

N PAVCNIK: If you look at the polls that ask people for their opinions regarding globalisation, there is less opposition in poorer countries than in developed countries. But I think the threat can grow if more people feel as if they are left out of this process or have not benefitted from this process.

SOURCE 3C

The article below was written by Lesetja Malope and appeared in the City Press on 28 May 2017. It is titled 'Gordhan Warns that Inequality Could Lead To Revolt'. It focuses on the impact that globalisation has had on many countries around the world.

Former Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan stated that globalisation is one of the major drivers of inequality in countries such as South Africa.

Gordhan highlighted that, with an increase in the level of stratification (grouping of people), the issue of inequality must be at the forefront of policies. He added that new forms of social safety nets should be created to reduce these social and economic divides.

It was through the effects of globalisation such as the divergence (difference) of incomes and the loss of jobs that has contributed to increased inequality in South Africa and other similar countries.

'There's a realisation that globalisation has actually resulted in winners and losers and that greater note needs to be taken of who are the winners and what percentage of the population they constitute, and who are the losers,' Gordhan said.

Gordhan also tackled the issue of radical economic transformation, saying the term is often misrepresented and it deceives people into believing that these initiatives (plans) will help the majority whereas it only benefits a minority. 'Economic transformation must be for the benefit of all 55 million South Africans,' Gordhan said. 'The others would actually say it in a way which is designed to mislead people … that if we do these extremely so-called radical things they would benefit, but ultimately the small elite (privileged) would actually benefit.'

SOURCE 3D

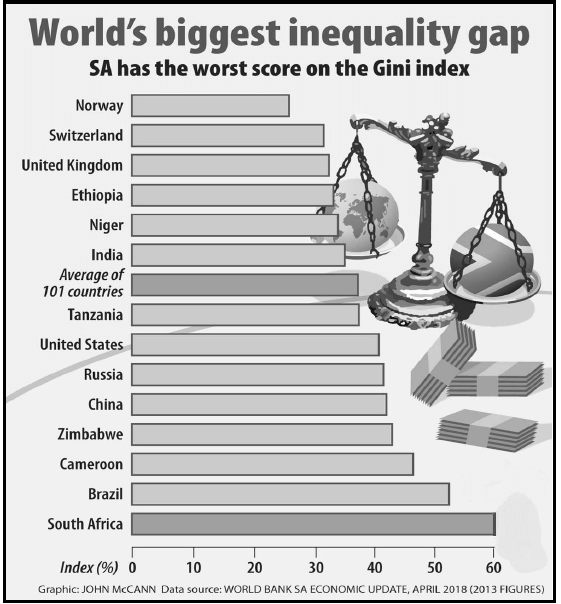

The graph below shows how globalisation has contributed to increased inequality gaps among various countries in the world. It appeared in the Mail & Guardian on 20 April 2018.

Gini index: Is used to measure the distribution of income of people living in a specific country. If the Gini index is higher, it means that inequality levels will be higher.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Visual sources and other historical evidence were taken from the following:

Mashabela, H. 2006. A People on the Boil: Reflections on June 16, 1976 and Beyond (Jacana Media)

http://azapo.org.za/the-june-16-uprising-ushackled-a-black perspective/.

http://sabctrc.saha.org.za/documents/hrvtrans/durban/56210.htm?t=%2Bnaidu+%2Bsurendra+%E2%80%98%2Blenny%E2%80%99&tab=hearings.

http://www.saha.org.za/news/2013/July/galley eugene de kock.htm.

https://city-press.news24.com/.

https://insights.som.yale.edu/insights/how-has-globalization-benefited-the-poor.

https://mg.co.za/article/2018-04-20-00-finding-wealth-in-a-sea-of-poverty.

https://www.iol.co.za/news/politics/families-hear-details-of-de-kock-deaths-6097.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/impact-globalization-developing-countries-fairooz-hamdi.

www.sahistory.org.za/pages/governance_projects/june16/june16.htm.

Meredith, M. 2005. The State of Africa. (Jonathan Ball)

The World, 17 June 1976