HISTORY PAPER 2 GRADE 12 ADDENDUM - NSC PAST PAPERS AND MEMOS JUNE 2022

Share via Whatsapp Join our WhatsApp Group Join our Telegram GroupNATIONAL

SENIOR CERTIFICATE

GRADE 12

JUNE 2022

HISTORY P2

ADDENDUM

QUESTION 1: HOW DID THE FORMATION OF THE UNITED DEMOCRATIC FRONT (UDF) HAVE AN IMPACT ON THE APARTHEID REGIME IN THE 1980s?

SOURCE 1A

This source is an excerpt from the speech made by Allan Boesak at the launch of the United Democratic Front (UDF) in Mitchell’s Plain, Cape Town in 1983.

‘Let me remind you of the three little words. The first is ‘all’. We want all our rights, not just a few token handouts which the government sees fit to give ... And we want all of South Africa’s people to have rights, not just a selected few, not just Coloureds and Indians. The second word is the word ‘here’. We want all our rights here in a united, undivided South Africa. We do not want them in impoverished homelands, we do not want them in our separate group areas. The third word is the word ‘now’. We want all our rights; we want them here and we want them now. We have been waiting so long. We have been struggling so long. We have pleaded, cried, petitioned too long now. We have been jailed, exiled, killed for too long. |

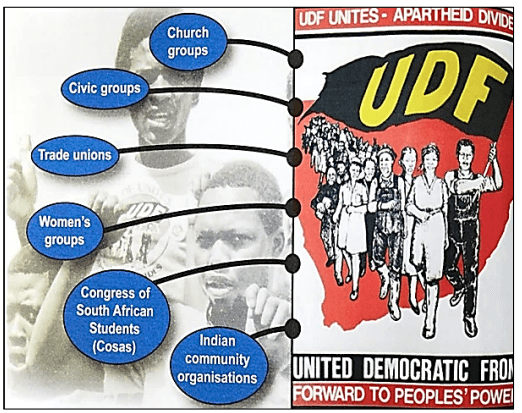

SOURCE 1B

The source shows the various organisations affiliated to the United Democratic Front (UDF).

[From www.ancarchives.co.za. Accessed on 14 February 2022.]

SOURCE 1C

The source below highlights the activities that the United Democratic Front (UDF) engaged in to challenge apartheid government policy in the 1980s.

The United Democratic Front’s (UDF’s) opposition to apartheid manifested (displayed) itself in a number of actions. Shortly after its formation, it launched a successful boycott action against the election of the (Coloured) House of Representatives and (Indian) House of Delegates. The UDF was involved in the organisation of a number of consumer boycotts and stay-aways. In 1983 and 1984, it launched the ‘one million signatures’ campaign, in which signatories were asked to voice their opposition to the so-called Koornhof legislation on black local government, as well as to the new constitution. However, the UDF’s greatest impact was at grassroots level where it created local structures that played a key role in the political education and mobilisation of the masses. At its second national congress, held in April 1985, it was decided to transform mass support into active participation, under the theme ‘From Protest to Challenge: From Mobilisation to Organisation’. Four months later this theme was extended to include a new slogan, ‘Forward to People’s Power’. The UDF’s strategy was to replace decision-making structures created by the government with a system of ‘people’s power’. It was equivalent to the establishment of ‘liberated areas’ in South Africa. The state headed off this threat and suppressed the general unrest in the country, which reached a peak in 1985, by calling a series of states of emergency. A large number of people were arrested in terms of security legislation. The UDF, in particular, was badly affected. Several key members of the organisation were murdered, including Matthew Goniwe (UDF organiser in the Eastern Cape) and Victoria Mxenge (UDF treasurer in Natal). Almost the entire leadership corps of the UDF was restricted in the period 1985 to 1987. [From https://omalley.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/index.php/site/q/03lv02424/04lv02730/05lv03188/ |

SOURCE 1D

The extract below focuses on the government’s reaction in repressing the leadership of the UDF.

| As the UDF grew, the apartheid regime tried every method at its disposal and every weapon in its arsenal to stop the spread of popular resistance. At times these methods were 'legal', following procedures laid down in the laws proclaimed by government. Other methods were acts of war against the population – they included assassination, bombs, and terrorism in the bitter meaning of the word. Some of the first measures the state tried to repress the UDF was to jail its leaders – by detention without trial, and by trial for political crimes. In August 1984, during the UDF’s highly successful boycotts of the Tricameral elections, the state detained 18 of the boycott leaders. In Natal they detained UDF national president, Archie Gumede (who was 78 years old); the UDF national treasurer Mewa Ramgobin, who was also publicity secretary of the Natal Indian Congress (NIC); President of the NIC George Sewpersadh; NIC vice-president MJ Naidoo; trade union leader and NIC member Billy Nair; general secretary of the South African Allied Workers’ Union Sam Kikine; and the national chairman of the African People’s Democratic Union of South Africa, Kadir Hassim. On September 13, 1984, six of the leaders who had gone into hiding – Archie Gumede, Mewa Ramgobin, MJ Naidoo, Billy Nair, George Sewpersadh and Paul David – took refuge in the British consulate in Durban. They deliberately went to the British consulate [From https://www.saha.org.za/udf/repressing_the_leadership.htm. Accessed on 23 January 2022.] |

QUESTION 2: HOW SUCCESSFUL WAS THE TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION (TRC) IN DEALING WITH THE DEATH OF MLUNGISI GRIFFITHS MXENGE?

SOURCE 2A

The following extract focuses on the assassination of anti-apartheid activist and attorney, Griffiths Mxenge, on 20 November 1981.

On 20 November 1981, Mr Griffiths Mxenge was found dead in a cycling stadium at Umlazi. Three Vlakplaas operatives namely, Commander Dirk Coetzee and ‘askaris’ (spy/sell-out) Almond Nofemela and David Tshikilange were charged and convicted of the killing. Coetzee, Nofemela and Tshikilange applied for amnesty for Mxenge’s killing. Nofemela told the Commission that the three men intercepted (captured) Mxenge on his way home from work on the evening of 20 November 1981. They dragged him out his car and took him to the nearby Umlazi stadium where they beat and stabbed him repeatedly. Nofemela told the Commission that Mxenge had resisted his attackers fiercely until he was struck on the head with a wheel spanner. He fell to the ground, and the stabbing continued until he was dead ... Then they took his car, wallet and other belongings to make it look like a robbery. Mxenge’s vehicle was later found, burnt out and abandoned, near the Golela border post between South Africa and Swaziland. On 15 May 1997, Coetzee, Nofemela and Tshikilange were found guilty of killing Mxenge. At the request of the Commission’s Amnesty Committee, sentencing was postponed until the Committee had reached a verdict on the applications ... [From www.justice.gov.za/trc/report/. Accessed on 28 January 2022.] |

SOURCE 2B

The following statement was issued by the Amnesty Committee of the TRC. It focuses on the reasons for the granting of amnesty to Dirk Coetzee, Almond Nofemela and David Tshikilange for the murder of Griffiths Mxenge.

The Amnesty Committee of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission today granted amnesty to Dirk Coetzee, David Tshikilange and Butana Almond Nofemela in respect of the murder of Durban attorney, Mr Griffiths Mxenge, in November 1981. The Committee said that while ‘there may be some doubt’ about the identity of those who ordered or advised Coetzee to kill Mr Mxenge, there was no doubt that Coetzee had acted on ‘the advice, command or order of one or more senior members of the Security Branch’ of the South African Police. The Committee placed on record its ‘strong disapproval’ of the conduct of the police in ‘arranging for the assassination of an attorney who was doing no more than his duty in providing adequate representation for persons facing criminal charges’. In its findings, the Committee said: ‘On the evidence before us we are satisfied that none of the Applicants knew the deceased, Mxenge, or had any reason to wish to bring about his death before they were ordered to do so. We are satisfied that they did what they did because they regarded it as their duty as policemen who were engaged in the struggle against the ANC and other liberation movements. It is, we think, clear that they relied on their superiors to have accurately and fairly considered the question as to whether the assassination was necessary or whether other steps could have been taken ...’ The three amnesty applicants were convicted of Mr Mxenge’s murder during a trial in Durban after their amnesty application had been heard. As a result of the granting of amnesty, it will not be necessary for the trial court to proceed with the question of sentence. [From www.info.gov.za/speeches/1997/08050w13297.html. Accessed on 28 January 2022.] |

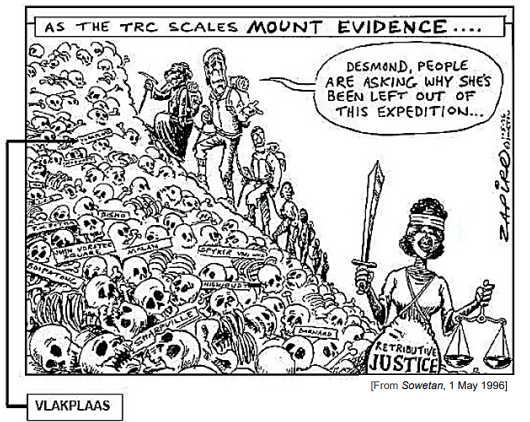

SOURCE 2C

This cartoon portrays Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Dr Alex Boraine climbing up MOUNT EVIDENCE. They were tasked to investigate the political atrocities that were committed between 1960 and 1994.

SOURCE 2D

The following report by the South African Press Association (SAPA) outlines the reasons for the Mxenge family’s opposition to the process of amnesty.

DURBAN, 5 November 1996 — SAPA MXENGE FAMILY OPPOSES COETZEE’S AMNESTY APPLICATION. The family of slain human-rights lawyer, Griffiths Mxenge, on Tuesday said the granting of amnesty to former policeman Dirk Coetzee, who has confessed to ordering Mxenge’s murder, would be a travesty (mockery) of justice ... Mxenge’s brother, Mhleli, 54, said Coetzee and his co-accused did not meet the criteria for amnesty as contained in the Promotion of National Reconciliation Act. Mxenge slammed the hearing, saying: ‘What annoys us is this interference with the due process of the law. We have battled hard to have Coetzee charged. Now these people are coming up with this ... amnesty hearing.’ In response to Coetzee’s statement that he was acting under instructions at the time, Mxenge said: ‘There is no evidence that killing their political opponents falls within the course and scope of their duties as members of the security police. I am, therefore, totally opposed to the granting of amnesty to Dirk Coetzee, Tshikilange and Almond Nofemela as this would be a travesty ...’ [From www.justice.gov.za/trc/media/1996/9611/s961105h.html. Accessed on 28 January 2022.] |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Visual sources and other historical evidence were taken from the following:

https://omalley.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/index.php/site/q/03lv02424/04lv02730/05lv031 88/06lv03222.htm

https://www.saha.org.za/udf/repressing_the_leadership.htm

www.ancarchives.co.za.

www.justice.gov.za/trc/report/

www.info.gov.za/speeches/1997/08050w13297.html

www.justice.gov.za/trc/media/1996/9611/s961105h.html.

South Africa since 1948 by C. Cupin, 2000, London

Sowetan, 1 May 1996