HISTORY PAPER 1 GRADE 12 ADDENDUM - NSC PAST PAPERS AND MEMOS NOVEMBER 2016

Share via Whatsapp Join our WhatsApp Group Join our Telegram GroupHISTORY

PAPER ONE (P1)

GRADE 12

NSC EXAM PAPERS AND MEMOS

NOVEMBER 2016

ADDENDUM

QUESTION 1: WHY DID THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA GIVE FINANCIAL AID TO EUROPEAN COUNTRIES AFTER 1945?

SOURCE 1A

The extract below outlines why the European Recovery Programme was implemented in Europe after 1945.

In the aftermath (outcome) of World War II, Western Europe lay devastated. The war had ruined crop fields and destroyed infrastructure, leaving most of Europe in dire (desperate) need. On 5 June 1947 Secretary of State George Marshall announced the European Recovery Programme. To avoid antagonising (provoking) the Soviet Union, Marshall announced that the purpose of sending aid to Western Europe was completely humanitarian, and even offered aid to the communist states in the East. Congress approved Truman's request of 17 billion dollars over four years to be sent to Great Britain, France, West Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Belgium. [From http://www.ushistory.org/us/52c.asp. |

SOURCE 1B

This source was written by an academic, Scott D Parrish, from the University of Texas in the United States of America. He analysed Evgenii Varga's (Soviet academic and economist) rejection of the Marshall Plan.

Varga put forward an economic explanation, arguing that 'the economic situation in the United States was the decisive (key) factor in putting forward the Marshall Plan proposal. The Marshall Plan is intended in the first instance to serve as a means of softening the expected economic crisis, the approach of which already no one in the United States denies'. Varga then went on to outline the dimensions (lengths) of the economic crisis, which he expected would soon overtake the United States. He anticipated a twenty per cent drop in production during this crisis, leading to the creation of a ten-million-man army of unemployed, and wreaking havoc (causing disaster) on the American banking system. As to the political effects of these economic difficulties, he concluded that 'the explosion of the economic and financial crisis will result in a significant drop in the foreign policy prestige (status) of the United States, which hopes to play the role of stabiliser of international capitalism'. [From https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/ACFB73.pdf. |

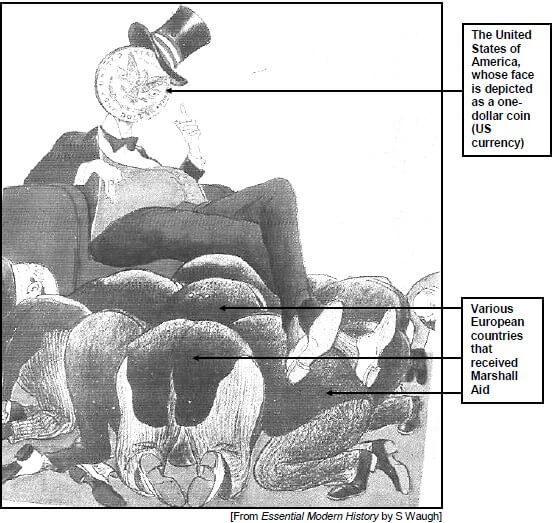

SOURCE 1C

This cartoon was published in the Krokodil, a Soviet magazine, in 1948. It depicts the effects of the Marshall Plan.

SOURCE 1D

This source was written by William R Keylor. He analyses the effects of the implementation of the Marshall Plan, both on Western European countries and the United States of America.

The economic consequences (results) of the Marshall Plan surpassed (were more than) the most optimistic expectations of its authors. By 1952, the termination date of the American aid programme, European industrial production had risen to 35 per cent and agricultural production to 10 per cent above the pre-war level. From the depths of economic despair the recipient nations of Western Europe embarked on a period of economic expansion that was to bring a degree of prosperity to their populations unimaginable (unbelievable) in the dark days of 1947. [From The Twentieth-Century World, An International History by WR Keylor] |

QUESTION 2: WHAT WERE THE CONSEQUENCES OF THE BATTLE OF CUITO CUANAVALE FOR SOUTHERN AFRICA?

SOURCE 2A

This source focuses on the opinions of historians Irina Filatova and Apollon Davidson, about the significance of the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale, which was fought in Angola between 1987 and 1988.

From the point of view of the Soviet military, the Angolans, Cubans, the post-apartheid South African government and many researchers, the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale was the turning point of the war, after which all the main goals of the war were achieved: South Africa had to withdraw its troops, Angola achieved relative peace and Namibia its independence. From the point of view of the South African military, there never was a 'Battle of Cuito Cuanavale', because, according to General J Geldenhuys, 'it had no strategic significance whatsoever. It played no role at all from whatever angle you look at it'. In fact, 'the Soviet alliance lost, because it did not manage to crush Savimbi and to demolish his capital, Jamba …'. [From The Hidden Thread. Russia and South Africa in the Soviet Era by I Filatova and A Davidson] |

SOURCE 2B

The extract below is taken from a speech by Fidel Castro (leader of Cuba) at a rally that was attended by thousands of people in Havana on 5 December 1988. Castro defended the involvement of Cuban troops in the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale.

The Angolan government had assigned us (Cuba) the responsibility of defending Cuito Cuanavale, and all necessary measures were taken not only to stop the South Africans, but to turn Cuito Cuanavale into a trap, a trap the South Africans ran into. In Cuito Cuanavale the South African army really broke their teeth (lost its power) … [From In Defence of Socialism: Four Speeches on the 30th Anniversary of the Cuban Revolution by F Castro] |

SOURCE 2C

This source by Christopher Saunders explains the role that the superpowers played in ensuring that the Angola/Namibia Accords (New York Accords) were signed. The Accords were signed by Cuba, Angola and South Africa at the United Nations headquarters in New York on 22 December 1988.

As Crocker (Assistant Secretary of African Affairs in the United States of America) had successfully argued over months would be the case, the final agreement provided something for each party involved … In the way the crisis was resolved, the two superpowers worked more closely together than ever, especially in the Joint Monitoring Commission that was established to ensure that the agreements were held to. [From Cold War in Southern Africa. White Power and Black Liberation, edited by S Onslow] |

SOURCE 2D

This photograph shows various leaders signing the New York Accords at the United Nations Headquarters in New York on 22 December 1988.

Seated from left to right are: Magnus Malan, Minister of Defence (South Africa), Roelof Frederik ('Pik') Botha, Minister of Foreign Affairs (South Africa), Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, Secretary General of the UN, George Shultz, Secretary of State (United States of America), Alfonso Van-Dunem, Minister of Foreign Affairs (Angola), António dos Santos Franҫa (Angolan representative), Isidoro Malmierca Peoli, Minister of Foreign Affairs (Cuba) and General Abelardo Colomé Ibarra (Cuba).

[From http://downloads.unmultimedia.org/photo/ltd/high/272/272982.jpg?s=4F0232819DA6CCCD391 EC97A2A1B59BD&save.

Accessed on 25 October 2015.]

QUESTION 3: WHAT CHALLENGES DID THE LITTLE ROCK NINE FACE DURING THE INTEGRATION OF CENTRAL HIGH SCHOOL IN 1957?

SOURCE 3A

This source focuses on the processes that occurred before the Little Rock Nine could enrol at Central High School in 1957.

… by the summer of 1957, school officials had selected 17 African-American students from over 200 applicants for enrolment at Central High School. School officials rejected many applicants because their grades were not high enough. Others were rejected because officials did not think they could handle the pressure of being a small minority in a school that was overwhelmingly white … Still other African students dropped out on their own after the superintendent told them that they would not be allowed to participate in sports or any other extracurricular activity. As resistance to integration became more vocal in the summer of 1957 in Little Rock and elsewhere, a number of parents withdrew their children out of fear for their safety. [From https://www.facinghistory.org/sites/default/files/publications/Choices_Little_Rock.pdf. |

SOURCE 3B

This source focuses on Elizabeth Eckford's experiences on 4 September 1957, her first day at Central High School.

The first scene Eckford saw when she got off the bus a block from Central High School was a sea of angry faces. She tried to walk to the school, but a jeering (mocking) mob blocked her path. All alone, her knees shaking, she pushed through the mob. She was trying hard not to show her fright. 'It was the longest block I ever walked in my whole life,' she said later. Eckford was one of nine students who had volunteered to be among the first African Americans to attend Central High School. When she left for school that morning, Eckford thought there might be trouble. But she didn't know that she would see hundreds of angry white people who had been waiting for her since early morning. Suddenly a shout went through the crowd. Elizabeth Eckford was attempting to enter the school. [From http://www.ahsd.org/social_studies/williamsm/The%20Mob%20at%20Central%20High%20School.pdf. |

*Nigger: A derogatory (offensive) term used to refer to African Americans

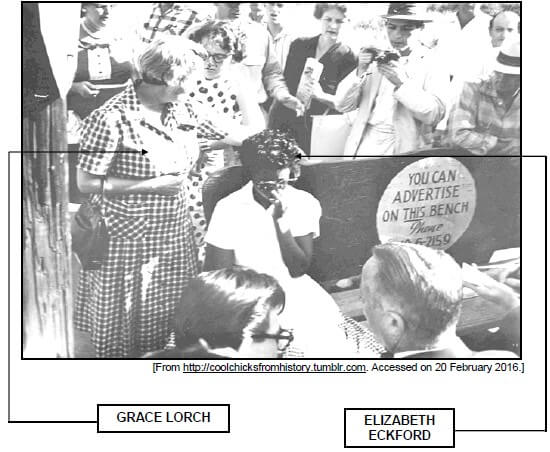

SOURCE 3C

This photograph shows Elizabeth Eckford at the bus stop outside Central High School, surrounded by a mob of white American segregationists. Grace Lorch, a member of the local National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), is seen with her arm around Elizabeth Eckford.

[From http://coolchicksfromhistory.tumblr.com. Accessed on 20 February 2016.]

SOURCE 3D

This extract focuses on events that occurred at the house of Daisy Bates on 5 September 1957. It was after the Little Rock Nine were prevented from entering Central High School the previous day.

… The Nine gathered at the Bates home. It was the first time Elizabeth had ever met Daisy Bates. Segregationists, reporters and Faubus were to accuse her of sending Elizabeth into the mob deliberately, to garner (gather) sympathetic publicity. Now Elizabeth let her have it, too. 'Why did you forget me?' she asked, with what Bates, who died in 1999, later called 'cold hatred in her eyes'. To this day Elizabeth believes that Bates, now lionised (praised) by everyone (a major street near Central High School has been named after her), saw the black students as little more than foot soldiers in a cause, and left them woefully unprepared for their ordeal. [From http://www.vanityfair.com/news/2007/09/littlerock200709. |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Visual sources and other historical evidence were taken from the following:

Castro, F. 1989. In Defence of Socialism: Four Speeches on the 30th Anniversary of the Cuban Revolution (Pathfinder, 1989)

Filatova I and Davidson A. 2013. The Hidden Thread. Russia and South Africa in the Soviet Era (Jonathan Ball, Cape Town)

http://coolchicksfromhistory.tumblr.com

http://downloads.unmultimedia.org/photo/ltd/high/272/272982.jpg?s=4F0232819DA6CCC D391 EC97A2A1B59BD&save

http://www.ahsd.org/social_studies/williamsm/The%20Mob%20at%20Central%20High%2 0School.pdf

http://www.ushistory.org/us/52c.asp

http://www.vanityfair.com/news/2007/09/littlerock200709

https://www.facinghistory.org/sites/default/files/publications/Choices_Little_Rock.pdf

https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/ACFB73.pdf

Keylor, WR. 1984. The Twentieth-Century World – An International History (Oxford University Press, New York)

Onslow (ed.). Cold War in Southern Africa. White Power and Black Liberation (Routledge, London)

Waugh, S. 1988. Essential Modern History (Oxford University Press, Harlow)